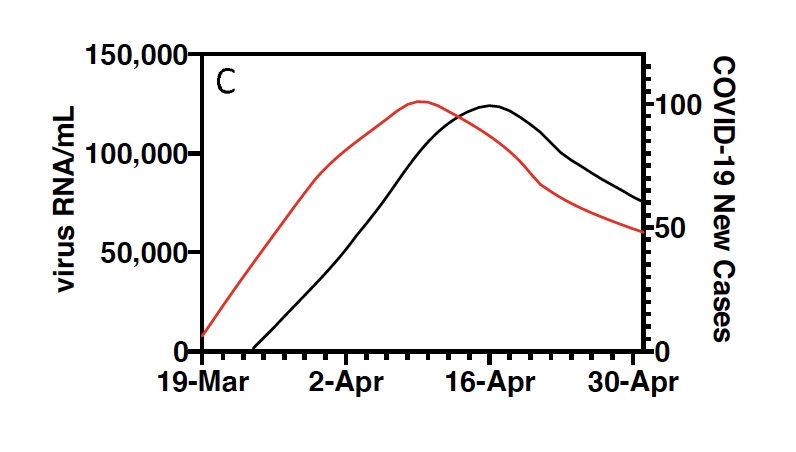

Above, from the Yale study: The red line represents the rise and fall of the COVID-19 outbreaks as detected in New Haven sewage. The darker line, seven days later, represents a similar curve of the outbreak as tracked in human testing.

A new study by Yale University of the COVID-19 virus in New Haven’s sewage sludge has found that testing human feces is a quicker and broader way to understand the pandemic in communities—a week faster than human testing and including even cases where people didn’t feel sick.

The study published Friday as a preprint (before peer review) compared sludge results from the settling tank at the East Shore Water Pollution Abatement Facility on New Haven Harbor to human testing and hospitalization rates for the New Haven area between March 19 and May 1. It found that the so-called curve of the epidemic’s rise and fall tracked each other but that the sludge results could be determined more quickly.

Testing continues daily.

Another outbreak going forward could be predicted through sewage testing seven days earlier than human testing and three days ahead of results on hospital admissions, said the lead author, Jordan Peccia, a professor of chemical and environmental engineering at Yale University.

Sewage testing has been used for years to understand drug use, eating habits, genetics, and diseases. Lead author Jordan Peccia’s past research has tested sewage for viruses including herpes, adeno virus, HIV, norovirus, and other coronaviruses like SARS and MERS. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor Eric Alm started a study of Cambridge, Mass. sewage in 2015 called Underworlds, and the Somerville, Mass.-based sewage testing company Biobot Analytics is now looking for COVID-19 in samples from sewage plants in 42 states.

The way to test people without symptoms

Sewage doesn’t lie. “When you test people,” he said, “you’re testing only the symptomatic people. You’re missing the asymptomatic fraction, which is significant. Meanwhile, they are giving their samples to the sewage treatment plant: samples from everyone served by the New Haven plant — 200,000 people. “We can do this for about $20 per test.” The East Shore sewage treatment plant serves New Haven, Hamden, East Haven, and parts of Woodbridge.

In the first weeks of the New Haven study, the Yale team froze sludge samples while they perfected methods to detect the virus. People who are infected—whether they show symptoms or not—shed RNA (ribonucleic acid) from the centers of COVID-19 molecules into their feces.

The sludge testing method involves the turning of the virus’s RNA (a single-stranded molecule) into DNA in the lab, which allows them to detect the virus at the molecular level.

In March when the team began, the sludge results weren’t available in real time. “We were figuring out how to do the analysis. We were storing it and checking,” Peccia said.

Peccia’s 11 co-authors are affiliated with Yale’s schools of public health, management, medicine, and nursing; its Institute for Global Health; and the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station.

“The city has been really remarkable in allowing us to continue to sample and taking any interest at all in our results,” Peccia said.

He said he hoped that widespread sewage testing could be a valuable nationwide method to understand the pandemic because 250 million people in the United States are served by municipal sewage plants.

“It’s certainly not going to replace (human) COVID testing,” Peccia said. “I want to be really clear: as an individual you know you are positive or negative and you can do contact tracing and quarantine yourself. That’s the gold standard.”

“There are two important things we get out of this testing,” Peccia said. “It’s another thing for cities, public health officials, municipalities, to look at as they’re making a decision about whether they’ve had 14 days of decrease in a row. The second one is it can be earlier than the testing data. It can answer this critical question we have right now: Are things going to go back up?”

Peccia said virus levels in New Haven sewage were so low by late May that “in the next set of analyses we will get some non-detects.”

What about combined sewage overflows and swimming?

It’s not known yet whether coronavirus can live in the diluted combined sewage overflow (CSO) discharges (untreated sewage mixed with rain) that still sometimes pour into water bodies in New Haven and five other cities. Peter A. Raymond, a professor of ecosystem ecology at Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, is sampling CSOs in the area. His results are not yet available.

Amy Kirby, a senior service fellow in the Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an April 27 webinar, “We think it is unlikely to present a substantial infection risk in wastewater.”

Jennifer Perry, assistant director of infrastructure management in the water bureau of the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, said DEEP has no evidence of how long the coronavirus can live in untreated wastewater. “So we recommend not swimming, bathing, drinking, or fishing next to or downstream of a combined sewer overflow for at least 48 hours after any storm.”

Peccia said, “I don’t want to go swimming in a water body that gets a CSO, but if I did, I wouldn’t worry about catching COVID. I’d be much more worried if on my way back from taking a sample, I stopped in the grocery store. It’s a disease that definitely goes from person to person, and the evidence suggests it’s much harder to be transmitted in the environment.”