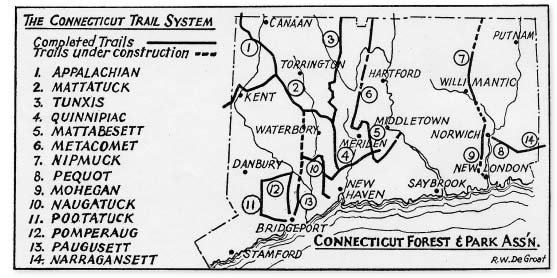

The Blue-Blazed Hiking Trails as shown in the Connecticut Walk Book, 1940. CONNECTICUT FOREST & PARK ASSOCIATION

written for Connecticut Woodlands

In December 1929, a handful of professional men who loved hiking began building the Blue-Blazed Hiking Trails in Connecticut

In December 1929, six men sat down at the Graduate Club in New Haven to plan a network of hiking trails in Connecticut. To look at the minutes of this first meeting of the Trails Committee of the Connecticut Forest & Park Association is to realize how much they had thought about their work beforehand.

In smooth succession, they adopted the philosophy of making “trunk line” trails and established four—a New Haven section, a Waterbury section, a Watertown-Litchfield section, and a Hartford section. They named chairmen of each.

They decided that they would allow others to work on the new Appalachian Trail segment taking form in western Connecticut. They settled on a method of trail work, using volunteers to work on localized sections.

Within two months they had named the Quinnipiac Trail in New Haven and chosen Witherall’s Atlas Paint No. 137, a certain shade of light blue, to mark the trails. The Quinnipiac Trail opened two months after that, in April of 1930. By the summer of 1932, they had blazed almost 200 miles of trails.

Back to the land

Since the 1890s, Connecticut residents had become caught up in a national momentum to walk in the backcountry. They were reacting to urban growth. In this state, as Guy and Laura Waterman have written in their book Forest and Crag, the urban growth was diffuse, with small cities scattered over the state—Waterbury, Bridgeport, Hartford, and New Haven—but Connecticut residents felt as eager as New Yorkers to escape civilization’s noise and fast pace. CFPA’s formation in 1895 was one of the early movements toward preserving and improving the natural landscape.

In January 1930, a few weeks after the Trails Committee pioneers met, CFPA held its annual meeting in Hartford. The speaker was Raymond Torrey, secretary of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society. He said that because people could drive cars every day, some of them wanted to walk for recreation.

“The automobile bids fair to reduce legs to more or less decorative appendages,” Mr. Torrey said, “but a few still walk for their soul’s good and to the body’s profit. To do so successfully they must be protected from automobiles, trolley cars and other 20th century inventions. All over the country, hiking clubs are springing up and reverting to the ways of our ancestors by building and traversing trails, blazed or otherwise marked in approved fashions, through what is left of our wilderness. We have a few trails sacred to the men on foot in Connecticut. The need and demand for more is growing.”

Educated mountain men

We don’t know much about the early trail pioneers. Obviously, they were all adventurous, generous of their time, and energetic.

The Trails Committee members were: Edgar Laing Heermance, a retired minister known for riding his bicycle; a Hartford trail enthusiast named Herbert C. Warner; Yale professor J. Walter Bassett; Hartford judge Arthur Perkins; Robert E. Platt of Waterbury; and Everett O. Waters, also a Yale professor.

Mr. Heermance, an 1899 graduate of Yale Divinity School, had spent time in the Catskills as a child. He built a shelter, the Heermance Shelter, on Mt. Wonalancet in the southern White Mountains of New Hampshire. He lived briefly in Minnesota but moved back to Connecticut in 1920, where he bought property, which he named Rocky Top, in Hamden. There, he rebuilt cabins and, with his children, blazed a 4-mile path just west of Sleeping Giant. Mr. Heermance marked this trail with light blue paint, the Watermans wrote, because the Wonalancet Out Door Club used that color.

By the first formal Trails Committee meeting, members knew they wanted four trail sections, in New Haven, Waterbury, Litchfield, and Hartford, and assigned chairmen to each section. Soon after, volunteers started routing these paths and marking the routes with light blue paint blazes.

Robert M. Ross, the secretary and forester of CFPA at the time, had laid out the Mt. Pico section of the Long Trail in Vermont while working there as state forester. He was enthusiastic about a Connecticut trail system and encouraged the Trails Committee, on which he sat as an ex-officio member.

Other early trail pioneers had started their push as early as 1916. One was Frederick W. Kilbourne of Meriden, a librarian and the associate editor of Webster’s International Dictionary. He blazed a route north of West Peak in Meriden’s Hubbard Park and east of Mt. Higby. By 1919, as the Watermans have chronicled, he had named it the Trap Rock Trail. He wrote about the trail in a memorandum, “Concerning Trails,” which he sent to the Connecticut State Park Commission.

In 1930, soon after the Trails Committee got started, Mr. Waters blazed the 21-mile Quinnipiac Trail with members of the Yale Outing Club. Other trail pioneers included Ned Anderson, who built much of the Appalachian Trail in Connecticut, Norman Greist of North Haven, who blazed trails across Sleeping Giant, Seymour Smith, Harold Pierpont, Kornel Bailey, and George Libby.

Out with golf, in with hiking

In Bristol, another trail pioneer attended a local meeting about trails in 1930. He was Romeyn A. Spare, a patent lawyer for New Departure, a division of General Motors that made ball bearings. He was a native of New Bedford, Massachusetts and a graduate of Harvard University and the law school at Georgetown University. Mr. Spare had given up his hobbies of sailing and golf in 1925 when he joined the Appalachian Mountain Club. In 1930 he began blazing the Tunxis Trail. For three decades, until 1961, Mr. Spare laid out and maintained this trail. The man who took over trail maintenance from him in the 1950s, George K. Libby, called him the Baron von Tunxis.

Mr. Libby said, in a written tribute when Mr. Spare died, that his mentor had taken to hiking “like a duck takes to water.”

Mr. Libby wrote, “I never knew Rome when he was in his prime. What a man he must have been!” But Mr. Spare was humble about his achievements. Mr. Libby wrote, “In 1961 when Rome retired from active trail maintenance he said to me, ‘George, I feel sorry for you. I had the easy 30 years on the Tunxis. I developed it when obtaining land permissions was easy; there were no housing developments, and no vandalism. Now all that is changed. Your 30 years will be years of disappointments and frustrations. You will live to see the trail disappear piece by piece.’ I thank God that he did not live to see this type of erosion continue because the process has already started.”

Mr. Libby was a pioneer himself. He was the first to involve young people in a systematic method of trail maintenance on the Tunxis. (The next issue of Connecticut Woodlands will describe this process, which Dan Casey took over in the mid-1980s.) Mr. Casey, who worked with Mr. Libby from 1973 until his death in 1986, said that Mr. Libby had a great respect for Romeyn Spare. He noted that Mr. Spare’s attitude about trails was that blazes should not be the only thing preventing a hiker from getting lost. “Rome Spare’s philosophy was, ‘If they don’t know what they’re doing, they don’t belong in the woods,” Mr. Casey said. “I heard this from George. George was much more forgiving.”

Original principles remain

The trails today are not exactly as the trail pioneers envisioned them. For example, the “Grand Junction,” where the Quinnipiac, Mattatuck, and Tunxis trails met north of Waterbury, still exists in Wolcott, but the junction no longer connects to the three trails. Many other trails have lost or relocated sections over the years. (CFPA continues to work with property owners to protect trail routes.) Despite the challenges, the pioneers who met in 1929 devised a trails plan that has changed remarkably little. They aimed for a network of trails, covering all areas of the state and easily reached from cities. They adopted the practice of using volunteer labor and working with property owners to keep the trails open.

John Hibbard, the former executive director, secretary, and forester of CFPA, said he identified a conservation ethic in the second and third generation of trail workers who learned from the trail pioneers. While the only original trail pioneer Mr. Hibbard knew was Mr. Spare, he got to know the others through the trail managers they had trained. Mr. Hibbard said that the early trail enthusiasts often used the word “eugenics” when discussing the conservation movement. Eugenics is the science of improving a breed or species. Perhaps their goal went beyond building and improving the trails, to altering the natural tendencies of people, away from pavement and toward the less predictable backcountry.

Sources for this story include the Connecticut Forest & Park Association archives; interviews with John Hibbard, Dan Casey, and Dale Hackett; an article, “Hiking Interest is Increasing in Connecticut,” published on July 9, 1932 in the Christian Science Monitor; an article, “Follow the Blue Blazes,” published in the Telephone Bulletin in July 1932; and Forest and Crag, by Guy and Laura Waterman (Boston: Appalachian Mountain Club, 1989), chapter 40.

About This Article

I am the editor of Connecticut Woodlands magazine, where this article first appeared in Spring 2004; I also write features for the magazine regularly. In 2004, the Blue-Blazed Hiking Trails of Connecticut marked 75 years of existence, mostly on private land. To subscribe to Connecticut Woodlands, one must join the organization that publishes it, Connecticut Forest & Park Association. See http://www.ctwoodlands.org.