The 1951 Popular Science excerpt from Rachel Carson’s book “The Sea Around Us”

yaleclimatemediaforum.org, August 9, 2012

From the perspective of the second decade of this 21st century, the climate literature of the pre- and post-World War II periods provide valuable historical insights: Not the least of which is that climate by then was already finding its way into popular literature.

The “next generation” on whose shoulders the weight of a warming climate will fall might be forgiven, given their documented drift away from traditional news outlets, for thinking climate change/global warming is the new kid on the science journalist’s radar screen.

It’s just not so.

The climate issue clearly lay firmly in public consciousness decades before Al Gore’s and Bill McKibben’s seminal works, Earth in the Balance and The End of Nature respectively. Popular writing by scientists who wanted the public informed about climate variations over time dates back at least seven decades.

This reality hit me afresh in 2009. While perusing a bookstore in Madison, Wisconsin, after the Society of Environmental Journalists (SEJ) annual conference, I found a book published in 1941, Climate and Man. It described climate change through the epochs for the farmer.

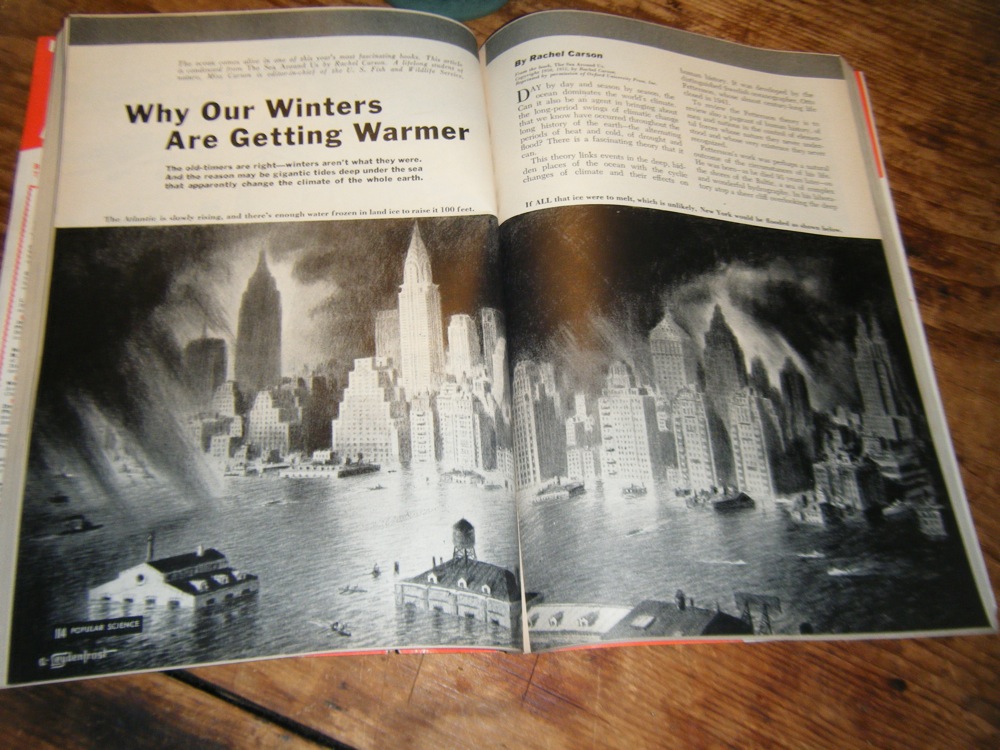

This respect for history hit again this year, with the convenient delivery in my living room of a box of old magazines from the town dump. Nestled among mostly automobile-related periodicals sat the November 1951 Popular Science issue. One of the features in that issue is “Why Our Winters Are Getting Warmer,” excerpted by the editors from Rachel Carson’s then-new book, The Sea Around Us.

“The old-timers are right—winters aren’t what they were,” the provocative subheading began. “And the reason may be gentle tides deep under the sea that apparently change the climate of the whole earth.”

People in the 1940s and 1950s appear to have been at least mildly curious about climate change and eager to plan for the future. These articles calmly lay out surprising conditions and predictions of what would be their changing day-to-day lives and routines.

That approach—calm teaching from scientists—remains a foundation for some serious journalists today. This approach—looking farther back in geologic time and weather history than the dawn of the industrial age, and regognizing the long-known reality that the sea is rising steadily—could still serve well today.

Climate from a 1941 Vantage Point

Climate and Man is a tome—1,247 pages—written and published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, subtitled 1941 Yearbook of Agriculture. This was one in the long-running series the USDA published. They were annual thematic books designed for farmers and those who plan for farming. The yearbooks were produced annually between 1894 and 1992.

The yearbooks of agriculture are more like snapshots of research in time, of course, but they are thorough snapshots, and they remain classics. Many no doubt still see it as a loss that USDA stopped publishing these books that had bridged scientific research on the land with non-scientists needing that information explained in clear words. Many of the yearbooks of agriculture remain on farmers’, writers’, scientists’, and hobbyists’ shelves for years after they came out.

Climate and Man weighs about 8 pounds, a disincentive to my carrying it home from Madison in these days of extra luggage equalling extra charges. I would have had to buy another rolling suitcase to carry it home.

But this year I searched for it and finally found a copy listed with an independent bookseller in Florida. The gray hardcover arrived with an inscription on the first page: “Madison, Wisconsin, 22 July 1997.”

Could this be the very copy I’d seen in Madison two years earlier, and 12 years after that inscription was penned? For sure, this book is pretty rare now, a relic of the earliest days of popular discussions of climate change. Might it just be the last available copy in North America?

One point in Climate and Man that leaps out from the perspective of 2012 is that it pays no heed to any notion that atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide were affecting the global climate. Not surprising given that the post-World War II industrialization, with its accompanying spurt in carbon dioxide emissions, was still a few years away. And with that spurt the warming we now trace back to thost post-war years and decades.

The book’s most enduring point is one perhaps still lost on people today: People ought to understand what’s going on with their local climates and plan their lives accordingly. This book includes separate detailed chapters about the localized climates in 1941 of all 50 United States. It includes charts and maps.

Richard Joel Russell, a professor of geography at Louisiana State University and a staffer at the time for the U.S. Soil Conservation Service, wrote a pertinent chapter, “Climatic Change Through the Ages.” He laid out the inevitability of change as a key principle.

“We are now at the tail end of an ice age,” Russell wrote on page 61, “and living in a period of crustal and climatic violences as great as any the Earth has known.”

Russell described two types of climatic patterns, according to geologists: “normal” and “glacial.” Normal climate is one in which no polar ice remains frozen in summer. In a glacial climate, he explained, polar ice remains frozen year-round.

People had not yet known a time when the climate was without frozen ice at the poles during the summer, Russell wrote. So the entire history of humans on Earth was during a glacial period, never a normal period. But “normal” does not mean “unchanging,” he counseled: In the geologic sense, a normal climate is the quiet time “between revolutions.” Such a state had not existed for a very long time, not since the very beginning of the Cenozoic era—that period of mammal dominance that started 65.5 million years ago.

In that post-depression\pre World War II period, scientists understood climate trends by studying varves—annual soil deposits in lake beds—tree rings, plant evidence in peat, and animal remains. The Agriculture Department, in Climate and Man, linked climate change to changes in Earth’s crust.

Russell dismissed theories that clouds, volcanoes, or increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere cause temperature changes. He wrote:

Much has been written about varying amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere as a possible cause of glacial periods. The theory received a fatal blow when it was realized that carbon dioxide is very selective as to the wave lengths of radiant energy it will absorb, filtering out only such waves as even very minute quantities of water vapor dispose of anyway. No probable increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide could materially affect either the amount of insolation [solar energy] reaching the surface or the amount of terrestrial radiation lost to space.

Rachel Carson in 1952, on Rising Sea Level

Pre-Silent Spring, Rachel Carson described patterns of the oceans in The Sea Around Us.

The magazine Popular Science printed excerpts of in November 1951, drawing most of the article from her chapter, “The Global Thermostat.” The editors illustrated the piece with black-and-white sketches of New York City with the sea lapping partway up the skyscrapers. (And this long before the scientifically flawed “The Day after Tomorrow” hit movie theaters in 2004.)

Carson relied heavily on an oceanographer, Otto Pettersson, who had died in 1941. His theory was that climate alterations were being driven by “events in the deep, hidden places of the ocean.”

Influenced by the position of the Moon and Sun, the submarine tidal action influenced “alternating periods of mild and severe climates,” Carson wrote, adding that the last time the world saw a mild climate, with little ice and snow, was in the year 550, and that such a warm climate would happen again in 2400. She noted that in about 1000, Vikings had sailed through northern oceans. By the 1500s, these routes were frozen and explorers abandoned them.

“But for the present, the evidence that the top of the world is growing warmer is to be found on every hand,” Carson wrote. The most dramatic changes were areas “directly under the control of the North American currents.”

She listed southern birds spotted in northern climes in the 1930s. She said cod and other fish had moved north to Greenland in about 1919. She described melting snowfields in Norway and shrinking glaciers in that country. And, about Antarctica, she said that the vast glaciers there were an enigma.

The job of evaluating the truth of these findings, now a half-century old, has gone to many others. These are the theories explained to the general public by writers of popular science with the staff of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and by Rachel Carson, who at the time was on the staff of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

What perhaps should matter to those today communicating the history and vagaries of what we today know as anthropogenic climate change is this: it’s not a new topic. We’ve been thinking about this for a long time.

About This Article

After I browsed through the Climate and Man book, the thought that this could make a good article bubbled around in my head for a while. Then this year my husband continued his perfect record of inspiring articles by dragging home the box that contained the Popular Science excerpt of Rachel Carson’s book, complete with the illustration of waves lapping on lower Manhattan. And I was off. Thanks to Bud Ward, my editor, for helping me bring this stuff to modern eyes.