Get This

Rest in peace Gregory L. Norris

Before the pandemic, I would attend the Berlin Writers meetings in a local office building downtown, when I was up in New Hampshire for my writing weeks. After the pandemic, the group moved to Zoom and was able to expand and embrace some of the writers who had moved away. Although I joined them only a few times a year, I drew on the optimistic inspiration Greg exuded. He had a way of helping by pointing out the strengths of a piece and then urging improvement from the strengths.

“Write, revise, submit,” he would say.

He wrote this blog post about my 2016 workshop, then called Writing from Nature. I held it that year at my in-laws’ summer cottage near Mount Monadnock, in southwestern New Hampshire.

He wrote this blog post about my 2016 workshop, then called Writing from Nature. I held it that year at my in-laws’ summer cottage near Mount Monadnock, in southwestern New Hampshire.

I will miss him and his dedication to writing as a paying career. He was such a pro.

Outdoor trudging as career builder: my interview with Mentors Collective

In an interview just posted on Mentors Collective, I talk about the many parallels between pushing one’s body and mind in the wilderness and challenging oneself in the workplace or at home.

Carrying my gear uphill, setting up camp, feeling cold and uncomfortable—sometimes almost hypothermic—means that I never mind when the elevators break, when I have to work long hours on a project, when I must go out in cold, snow, wind, or hurricane. I believe I grow when I’m uncomfortable.

I hope women reading it will be inspired to try going out on their own in natural places. I hope all people will realize that pushing beyond what they thought they could do, physically, brings huge benefits to all of life.

Contact me if you’d like a signed copy or to hear more from me at your group or community event.

Solo hiking as personal growth: me on Vision Pros podcast

How do you define courage? What does grubby rock scrambling have to do with personal growth? What obligation does a woman have to teach resiliency to daughters? I talked about all these and more on this new episode of Vision Pros.

Short fiction debut

Running Wild Press’s new Short Story Anthology arrived yesterday with my story, “Pumping Station Road.” It tells the story of Lloyd, a lobbyist and trail runner whose big solo run of the length of Connecticut from east to west hits a snag. Lloyd believes he cares deeply about living an ethical life that respects community. But trying to complete this run leads him smack into some ethical quandaries when his girlfriend, a better runner, falls ill and can’t help him.

This is my first published fiction, although I’ve been writing stories for a while. I sold another story about a hunter whose truck breaks down and needs a ride to a book that is yet to come out. Short fiction allows writers to inhabit a character’s mind either wholly or in a limited way. I loved showing only what Lloyd could see and believe while still hinting at a wider reality by writing in the third person.

I felt like celebrating when my copy of the story collection arrived yesterday. Order a copy for yourself or a reader who enjoys fresh voices in fiction.

Thanks to Benjamin White, the editor, and the LA-based Running Wild Press.

The ever moving river of ideas

Writers sometimes feel that time evaporates before they can write, or that they need something to tap into the river. That the rest of life interferes, or that when a free stretch of time does finally open up, the idea river has run dry.

It has not run dry. My workshop Writing with Woodside sends writers into the river of ideas. I started offering my workshops a decade ago because I wanted an alternative to workshops based on revision: taking a manuscript and revising it in a class setting. My workshop is different. You come with a blank notebook and an open mind. You come to move through nature and write new material with my encouragement. You do not have to show up with a piece of work unless you want to. You need not “workshop” anything. Writers are invited to read out loud bits of what they draft throughout the weekend.

The next workshop is at Rockywold-Deephaven Camps on Squam Lake in central New Hampshire, June 12-15. Rates are reasonable and include the workshop, delicious meals, comfortable rooms in a cabin, our own dock, and access to trails and the lake. Join me! Sign up here.

“I’ve attended dozens of writing retreats and workshops, and Christine’s ranks at the top of the list. During that unforgettable weekend, she challenged us to write and experience life beyond our comfort zones. The result was forward evolution in our writing. Not only highly recommended, but a must-do for writers seeking to connect with the natural world, their muses, and their own souls.”

—Gregory L. Norris, novelist and screenwriter, Monsterland (October 2024, Van Velzer Press)

Book Talk October 15 at Bank Square Books

Save the date. I will give a talk and reading from my wilderness memoir Going Over the Mountain at the new location of Bank Square Books, 80 Stonington Road, Mystic, Connecticut, on Tuesday, October 15 at 6 p.m.

Going Over the Mountain: One Woman’s Journey from Follower to Solo Hiker and Back maps the evolution of a woman through backcountry adventures. It’s a story of evolution that reaches out from the wilds and into the hearts of all who seek to understand who they really are.

Blair Braverman, author and adventurer, calls Going Over the Mountain “a reflection on entering the woods as a follower, a solo traveler, a parent, and in community, for anyone who’s turned to the trail for comfort, or dreams of trying someday.”

Erica Berry, author of Wolfish, says this book “evocatively weaves vignettes from her intrepid decades on the trail.”

Climber and author Laura Waterman says, “This deeply insightful memoir is wise and funny, easy to pick up, and impossible to put down.”

And Elissa Ely, whose essays explore interactions in the mountains, had this to say about my book: “Whether she is writing about her love for an old cooking pot or for camping in a storm with her daughters, reading T.S. Eliot poetry on the Appalachian Trail or racing to climb each New England state’s highest mountain in 48 hours, her life among the mountains reinds us eloquently that life devoted to these places will save us.”

I’ll be on Hiker Trash Radio June 3

Pick up your favorite trail snacks and get ready to hear my hiking story on Hiker Trash Radio, the podcast where Doc introduces you to all sorts of characters who have taken the trail into themselves and become different people in the process. The episode with me posts on June 3.

I’ll talk about my two trail names, why I hike with one pole if that, my love of crabwalking, taking out my daughters onto the Appalachian Trail in spring’s tempests, the glories of hiking partners, knowing when to go alone, and more.

Going Over the Mountain reading at Wesleyan RJ Julia Bookstore

Join me for my next reading from Going Over the Mountain, Wednesday, October 18 from 5-6 p.m. at Wesleyan R.J. Julia Bookstore! Sign up here. Get your own copy and have it signed.

I will read you a story. A chapters other audiences haven’t heard yet. I’ve read to audiences about my clueless following of my boyfriend; about leading my kids past dead horses, about encounters with giant snowshoe hares.

Next: I’ll read another chapter about another experience of immersion in the wilderness!

These journeys changed me and my relationships, scared me and gave me courage, delivered wild joy and sobbing, helped me like myself, and more.

I will answer questions. Do my daughters still like to walk in the woods after all the years I pulled them out there with me? Was I scared going alone? Did hiking the whole Appalachian Trail strengthen my marriage or put cracks in it? And more.

Launch party on September 10 at Breakwater Books. Reading September 13 at the Norwich Bookstore in Vermont

Breakwater Books will host a launch party on Sunday, September 10 at 5 p.m. at their store at 18 Whitfield Street in Guilford, Connecticut. Thank you, Breakwater!

The Norwich Bookstore will host my next reading and talk on September 13 starting at 7 p.m. The bookstore is at 291 Main Street in Norwich, Vermont, between the Green Mountains and the White Mountains. The store is situated just east of the Appalachian Trail and just west of the Connecticut River, the town of Hanover, New Hampshire, and Dartmouth College.

Preorder your copy now, and spread the word.

Health reporting that made a difference

Over the past several years, I wrote environmental health stories for the Connecticut Health Investigative Team. C-hit.org’s founder and editor Lynne Delucia decided to stop publishing new material as 2022 came to a close. Delucia edited and inspired journalists at the Hartford Courant, New Haven Register, and c-hit over her distinguished career. She pulled some of my best work out of me. Thank you, Lynne.

Over the past several years, I wrote environmental health stories for the Connecticut Health Investigative Team. C-hit.org’s founder and editor Lynne Delucia decided to stop publishing new material as 2022 came to a close. Delucia edited and inspired journalists at the Hartford Courant, New Haven Register, and c-hit over her distinguished career. She pulled some of my best work out of me. Thank you, Lynne.

With the assistance of a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists, c-hit worked with me on my three-part series on legal sewage overflows in Bridgeport, Connecticut’s largest city. The stories in “Legal but Tainted” won two journalism awards and may have inspired the progress the city, state, and federal government have made to upgrade the aging plant and its pipes.

My other stories for c-hit covered a wide range of environmental health troubles, from how easy it is to drown in unguarded public swimming areas to mosquito-borne illnesses, Lyme disease, obesity, and testing sewage for signs of Covid-19.

The stories will remain posted at c-hit indefinitely. March on over and read some of them! Here are mine.

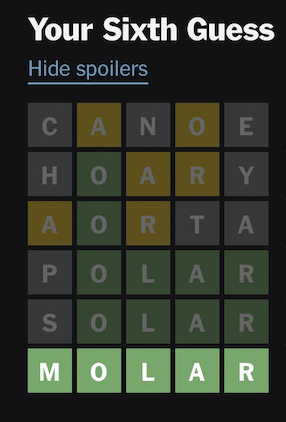

Morning person? No. Night owl.

This morning, I tried solving the daily Wordle puzzle before I got out of bed. It took me three times as long, and I almost didn’t get it. I actually had predicted this might be true. I wake up slowly. My brain just seems less flexible until a few hours after I wake up. Is that true for you? Or are you at your best the moment you open your eyes and it’s all downhill throughout the day? That’s my husband’s assessment of his productivity pattern.

He is a morning person. I’m a night owl. We converge during the evening hours to connect in conversation. As the years have gone by, though, I’m not the same kind of night owl I used to be. I will sit up doing some work or reading after my husband goes to bed. But only for a few hours. I need to get seven hours of sleep. I don’t try to stay up all night the way I could back in the early days.

But I am very productive mentally from about 4:30 to 7:30 p.m. I try most work days to be sitting at my desk between those hours so I will receive the magic.

On days I decide to stop writing or editing before 7:30, I do so by choice. I need a good reason. Otherwise, I know I can complete drafts during that time. I know I can edit stories for Appalachia journal with a clear head then. It doesn’t feel hard.

I won’t push anymore through periods my mental focus goes fuzzy. Like 3 p.m. My father-in-law used to say that in hell it is always 3 o’clock in the afternoon. I do not work well at 3 p.m. Everything takes twice as long then. I might instead get up and take a walk. For years I used to push through those times. No more.

Understanding one’s productive times and fuzzy-brain times can open many doors to moving happily through new writing projects. Not feeling bad that I’m not a machine has helped me relax into the kind of work I feel truly called to do.

Writing below a mountain

A birch and a pine grow next to each other below Mount Cardigan, Alexandria, New Hampshire.

I just returned from leading a writing workshop for the Appalachian Mountain Club. The AMC and I began Writing from the Mountains in 2016. The year before, we had brainstormed the workshop but had to cancel with too few signups. That changed dramatically from 2016 onward. The only year we didn’t run it was during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. In 2021 I ran the workshop at the Highland Center; we wore masks inside. This year we returned to the workshop’s roots at Cardigan Lodge.

Our group included men and women of all ages—poets, novelists, nonfiction writers, those just beginning their writing journeys and those who have published books and pieces. Everyone came with an open heart and mind.

Saturday everyone took a solo ramble, without notebooks or camera, on one of the many trails that begin adjacent to the lodge. After about two hours they returned, and I guided them in three writing excercises. First they created a kind of timeline of the morning’s evolution, in four stages. Next they made a free-range list of every detail they could recall. Third, each drafted a letter to a difficult person, telling the person about the morning.

Saturday afternoon we discussed two essays, one by the writer Sandy Stott about bushwhacking around Cardigan. He has explored that ridge his whole life. Sandy is a former Appalachia journal editor and the current editor of the journal’s Accidents section. The next essay was one of my favorites for this workshop, “Reconnaissance,” by Colin Fletcher, about a failed river crossing in the Grand Canyon. After this writer Elissa Ely, who was assistant workshop leader this year, led us in an exercise: we went back out to our morning routes for 10 minutes and explored our peripheral vision. What had we missed to the right and left of the trail?

Saturday evening, writers read some of their new work from the day’s writing. Sharing first drafts is an act of trust and courage, and the sentences were beautiful and inspiring. The positive energy of the group provides the impetus to keep going with a work. These are the moments that can make or destroy a writer.

I know we made a lot of new beginnings here.

Sunday morning we took short field trips. I instructed everyone to find one place, sit or stand there and observe. Write, sketch, photograph, and listen. Inside, we reported sightings of barred owls, salamanders, river otters, birches growing next to conifers, ice crystals on bridges, and more.

New fiction in next year’s Running Wild Press Anthology

My short story, “Pumping Station Road,” about a trail runner whose ambition to run the entire width of Connecticut from east to west causes havoc with people he loves, will appear in the seventh Running Wild Press Anthology of Stories coming out in October 2023 from this California-based publisher. I am more than a little excited about publishing short fiction.

A year may seem like a long time to wait, but in the world of good books, it isn’t. Meanwhile, consider getting hold of Running Wild Press’s sixth Anthology of Stories. That one just came out this month.

Pre-order the sixth anthology here while you wait with me for the seventh to come out next year.

Update, early spring 2022

Above: Annie Gribbins with some of her husband’s emergency rescue gear, which has inspired us to think of new coping strategies as the pandemic winds down.

My sister Anne Woodside Gribbins and I have published a new essay about coping strategies in the pandemic age. Find it here.

Climate activists and researchers say disaster planning fails to consider a community that is often marginalized and vulnerable, gay people. Read my interviews with Leo Goldsmith and Adrian Huq here.

Two weeks ago, as thin ice layers melted on the newly fallen leaves in New Hampshire’s Crawford Notch, I said goodbye to a group of writers who’d spent the weekend with me for another Writing from the Mountains. These creatives were at varying stages of ideas and projects. They hiked on newly frozen paths, wrote new thoughts and memories back inside, read and discussed essays on landscape, and shared their work. Sunday we practiced close observation of trees, ice, dirt, fungi. Thank you, writers! I learn so much from you. Thanks also to the Appalachian Mountain Club for running all the practical parts of this workshop: lodging, food, and our terrific guide and writer, Clare.