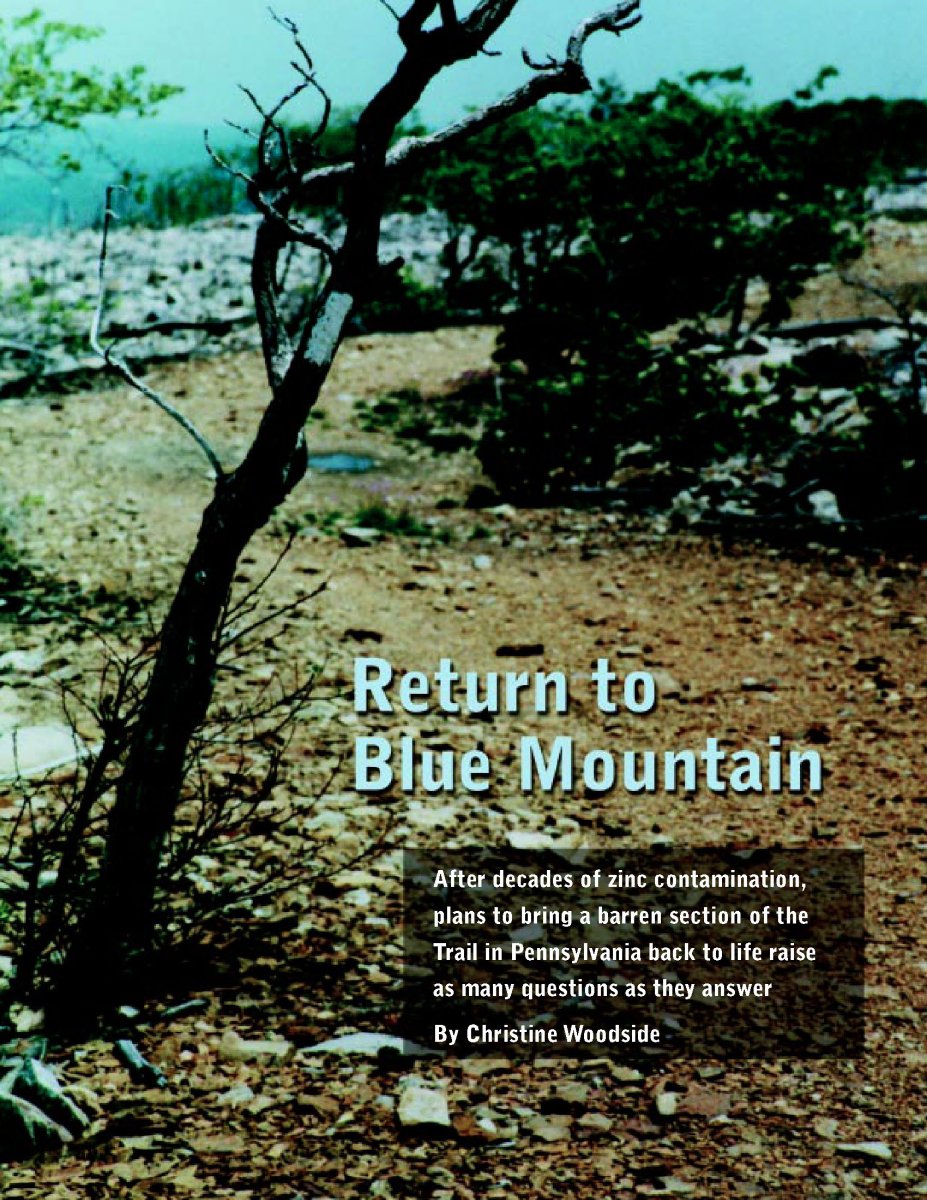

Cover page shows the denuded landscape of Blue Mountain near Palmerton, Pennsylvania

Written for Appalachian Trailway News

Fourteen years ago, in 1987, when I followed the northbound Appalachian Trail up the cliff over the Lehigh River near Palmerton, Pennsylvania, the view reminded me at first of the Trail above treeline in the White Mountains—a blue sky framing bare rocks above. Then, I quickly realized it was an artificial treeline, one created by poison.

On top of the low ridge of Blue Mountain, my companions and I grimaced as we stepped over the rocks and began crossing a plateau of rubble that stretched as far as we could see.

Not one plant grew. Petrified trees stuck up here and there. Otherwise, it looked like the moon.

Sometime before the Great Depression, Blue Mountain’s forest began to die. Between 1898 and 1980, smelteries to the north and west produced zinc products, heating and melting zinc for alloys and pigments. Most of the damage was done by the mid-1940s, local residents say. The smokestacks, operating legally, sent particles and vapors of uncaptured zinc, cadmium, and lead into the air. They covered the forested hills. Sulfur, a byproduct of the smelting, also stressed the forest. The heavy-metal pollution killed vegetation, exposing rocks on the mountain and speeding erosion. In the valley, the soil and Aquashicola Creek (which runs into the Lehigh River here) became contaminated with the heavy metals. Since 1983, the city, 2,000 acres on both sides of Lehigh Gap, the creek, and a 2.5-mile-long bank of slag and cinders all have been on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s “Superfund” list—the government’s roster of industrial wastelands slated for projects to reverse environmental damage and to force owners to take responsibility.

Adding Palmerton to the list was easy, since it meant a promise to try to protect the health of Palmerton’s residents (some of whose children had elevated lead levels in their blood and whose lawns wouldn’t grow) and to try to grow something on the mountain. Fixing the damage has turned out to be something of an ordeal.

Today, the U.S. government and a company that once owned the zinc smelteries in Palmerton are testing a method of planting that isn’t guaranteed to grow back a forest, but that seems the only option.

Next fall, or soon after, a small plane, buzzing low over the most ecologically damaged section of the mountain, over which the Appalachian Trail runs, will drop a layer of fertilizer and seeds on top of what has looked more like a lifeless world than the Earth. It could end up closing the Trail or causing Trail managers to reroute it temporarily along busy roads.

In trying to assign blame for this scene, the EPA has had to deal with the fact that most of the people who had much to do with the Palmerton pollution are dead. Even the New Jersey Zinc Co., which owned the plants, was absorbed into Gulf & Western in 1966. In the early 1980s, Horsehead Industries, Inc., of Monaca, Pennsylvania, the parent company of the Zinc Corp. of America, acquired the Palmerton plants from Gulf & Western. After selling the Palmerton facility in 1989, Gulf & Western became Paramount Communications, which later was merged into Viacom International, the entertainment company that owns CBS, MTV, Simon & Schuster, and a majority interest in Blockbuster Video. Another company that found itself attached to the Palmerton mess was TCI Pacific Communications, Inc., which bought a portion of Paramount.

During its heyday in the 1940s, New Jersey Zinc Co. ran two smelters, the east plant and the west plant near Lehigh Gap. The plants processed crude zinc oxide or zinc sulfide, which it brought in from mines in New Jersey, into alloys for brass, for galvanized steel, for zinc oxide, and other substances. In the 1940s, it employed about 3,000 people. And, up on the mountain, people sometimes burned some of the trees to encourage blueberry bushes to grow.

The Palmerton plants stopped smelting zinc in 1980. In the one zinc facility left in Palmerton, the so-called “east plant,” Horsehead has been recycling zinc from sources that include the scrap left when steel is galvanized. From two miles north of Lehigh Gap on the A.T., a hiker can see this plant, to the north of the Trail in Palmerton. There, Horsehead employs a few hundred people, the company said. Its air emissions are a fraction of what they once were, not only because the operation is so much smaller, but also because they must comply with modern emissions standards.

In 1988, the EPA ordered the successors of New Jersey Zinc to take responsibility for the pollution. It named TCI, Viacom, and Horsehead the “primary responsible parties” in an order to reverse the damage. From 1990 to 1995, Horsehead hired workers to build about 60 miles of roads on the slope of Blue Mountain between Palmerton and the area around the Appalachian Trail. From trucks, it then spread a mixture of sewage sludge, ash from incinerators, and seeds on the lower part of the mountain that today looks green. EPA’s order was to make sure tree seedlings took root along with grass. Horsehead was not able to fulfill that order.

Today, the EPA says that tree growth early on was an impossible goal. “It’s very difficult to get the trees to grow,” said Charlie Root, remedial project manager at the EPA’s Philadelphia office. Over time, he said, the agency believes a forest will grow back on its own.

“We’re coming to the conclusion that we’ll settle for a meadow environment rather than a forested environment,” said Eugene T. Dennis, a geologist and environmental scientist who manages the Palmerton project with Root.

Horsehead also has worked to cover and plant seeds on the cinder bank along the creek and to divert away from the cinder bank contaminated rainwater that washes down the mountain. EPA, meanwhile, removed soil and cleaned houses in Palmerton to remove lead dust after tests a few years ago revealed children in town had high lead levels in their blood.

In the summer of 2001, I climbed Blue Mountain again. The ridgetop still looked like a gravesite, but one with a few green spots. Ferns, small trees, bushes, and grassy patches clung to little patches of soil that must have somehow blown in. The Trail on Blue Mountain follows an eastwest route—a northbound A.T. hiker actually walks east along the ridgeline. Standing on the Trail, looking due north toward Palmerton, I saw a swath of dark green on the lower slope. The green ended in a dramatic line about 600 feet away from the Trail. That was the place where, in the mid-1990s, Horsehead Industries stopped spreading the mix of sewage sludge, seeds, and fly ash from the network of roads it built for the job. That part of the mountain looked green, and where I was hiking, things were clearly trying to grow in the contaminated soil. Twisted trees bent over near the path. Their leaves looked a little like sassafras, but some were large and some were tiny, some had a notch and some didn’t. All were mottled with yellow and brown-edged holes in early August.

A little farther on, I came to birch trees that looked healthier. The landscape was still mainly a colorless mass of white rock and dead trees. The trees had never decomposed because the zinc acted as a sterilizer, killing off all the biological life that would have normally broken the wood down into mulch. A mile farther, a small blueberry bush growing next to the Trail was full of blueberries. The leaves were red.

On part of the mountain, the revegetation is starting to pay off, according to Dolores Ziegenfus, who manages a communitygroup that tries to get information to the public on the cleanup. “This spring was the first time I noticed a dramatic difference— natural tree growth,” Ziegenfus said. Her Palmerton Environmental Task Force holds monthly meetings for the community and manages a lead-abatement program for U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The question, of course, is what will happen to the rest of the mountain. Once Horsehead spread the seeds on the lower mountain, it did no more on the rest of the mountain. In 1998, the Environmental Protection Agency sued TCI Pacific, Viacom, and Horsehead, demanding they pay $12 million to the government for what it has spent so far on the project and demanding that the companies accept liability for the future work—including revegetation of the area around the Appalachian Trail.

EPA says that the lawsuit hasn’t been resolved nor has it been withdrawn. In 1999, the agency ordered Viacom and Horsehead to do something about the rest of the mountain. Viacom agreed, but Horsehead did not. According to EPA, Horsehead attached several conditions to its offer to do anything further on the mountain, which the agency interpreted as a refusal, Root said. William Trainer, vice president of business development for Horsehead’s Zinc Corporation of America, said, “Horsehead has fulfilled its obligation for revegetation.” He said that Viacom “has full responsibility for the remaining acreage.”

Viacom doesn’t agree. The company sued Horsehead a decade ago, claiming that, when Horsehead acquired the plant, it promised to indemnify Viacom from the responsibility of dealing with the zinc pollution. The legal battle has yet to be resolved, but Jeff Groy, vice president and environmental counsel for Viacom, said the two companies continue to communicate over other aspects of the Palmerton clean-up and about a clean-up going on at another former zinc plant in Illinois.

“Under the Superfund statute, we have an obligation to revegetate Blue Mountain, but we are pursuing the costs we have incurred or will incur,” Groy said.

Last year, Viacom hired a contractor, Adrian Brown Consultantsof Denver, Colorado, to begin work on the project to plant vegetation on the remaining 1,000 acres of Blue Mountain, which includes the A.T. and land directly around it. Most of the section is east of Lehigh Gap, and some of it is directly west (southbound on the Trail from the gap).

In spring 2001, Adrian Brown Consultants spread various mixtures of fertilizer and seeds, using a helicopter on twelve one-acre test plots on the section of land west of the gap. The test plots are on private land, well off the A.T.

If enough grows on the plots—something to be determined later in the fall—and if EPA approves the application, the agency will allow Viacom to drop fertilizer and seeds from small airplanes directly onto the A.T. That could happen as early as fall 2002, said EPA’s Charlie Root.

Hikers could expect to find the Trail in the entire Palmerton area to be rerouted or closed, said Don Owen, environmental protection specialist for the Appalachian Trail office of the National Park Service.

“We would probably have to either shuttle hikers around the area or implement a temporary relocation of the Trail,” Owen said. “That would take the Trail completely off the mountain during remediation. There’s probably no way around it.”

But, Groy of Viacom said it’s not certain now that the Trail would have to close for a long period. He suggested it would close only for a month or so while the planes are dropping the fertilizer.

The timing of the revegetation—whether it will be next fall or later—rides on whether anything grows on the test plots before winter sets in. As of late summer, grass had sprung up on a few of the plots, while others looked bare, several observers said. All the involved parties were planning to watch the seeded areas through the fall.

Groy said that dropping fertilizer and seeds by plane had worked out well. “We’ve talked to people who helped to revegetate after Mount St. Helen’s. It’s a tried and true approach for agricultural applications,” he said. “Hopefully, it will save time and be more feasible given the terrain we’re having to deal

with.”

Owen said that he and representatives of the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, U.S. Public Health Service, and the Appalachian Trail Conference are not convinced that the test plots were a success. Representatives of those organizations meet from time to time with the companies and the EPA to offer their perspective on the problem.

“I would say that there was fairly minimal growth,” Owen said. “I think there is a lot of work that needs to be done, a lot of scientific work that could be done before we implement a remediation plan. I think that Horsehead Industries’ previous work was fairly well-documented. Although not entirely successful, they did succeed in getting some vegetation to grow on the mountain.”

Owen said Trail advocates are not completely satisfied with Horsehead’s work on the other section of the mountain, but that they recognize it had some merits. “I think we’d like to look at that, too,” he said, “but I think, if we were talking about remediation at that standard, we’d have a basis from which to work.”

Michele Miller, associate regional representative of the Appalachian Trail Conference’s mid-Atlantic office, agreed that there were good aspects of Horsehead’s work on the mountain. It used sludge, which is heavy and can’t be blown off the incline; Viacom’s new plan uses fertilizer, which is lighter, she noted. Groy of Viacom said they could not find a source for sludge.

Miller said that ATC and Trail advocates submitted a long list of questions to EPA. Those questions included queries about hiker safety walking through the area after the fertilizer is dumped. So far, EPA has said it believes hikers are perfectly safe walking through contaminated soils—they just shouldn’t take up residence on Blue Mountain. But, after the fertilizer mixture lands on the Trail, the Trail advocates said they are not sure if it will be safe for hikers.

The Conference’s questions also included what would happen to two springs east of Lehigh Gap and, most important, what the company will do if the fertilizer and seed drop doesn’t work, and nothing grows on the mountain.

“I think maybe the number-one frustration is not feeling like we’re getting answers to the questions we’ve provided,” ATC’s Miller said.

About This Article

This appeared in Appalachian Trailway News, a magazine published for many years by the former Appalachian Trail Conference, the organization that coordinated the volunteer maintainers of the Appalachian Trail, the hiking route from Georgia to Maine. Since the project to protect the trail corridor is more or less compete, the group is now called the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. It publishes a different magazine now. Trailway News was edited by the competent Judy Jenner, a former newspaper reporter and today the owner of a yoga studio in West Virginia.