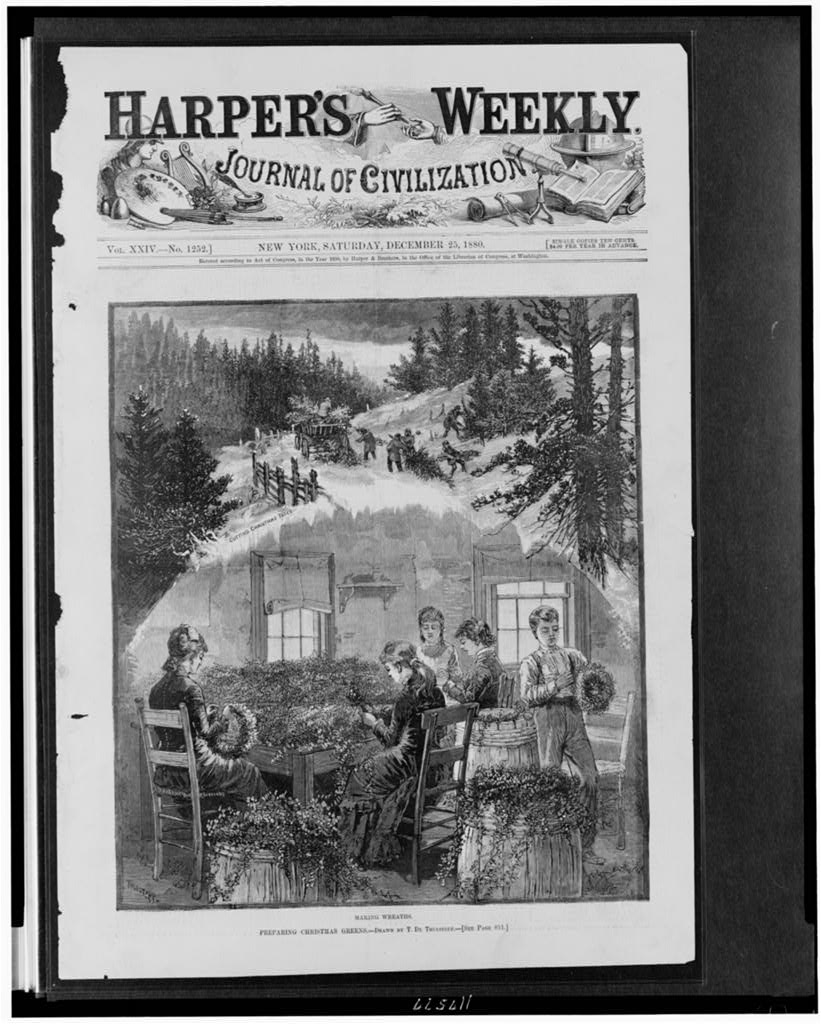

Harper’s Weekly, December 25, 1880. People making wreaths.

I am not a grinch—really. But I can’t help but think of Thorstein Veblen, the man who gave us the term “conspicuous consumption,” at this time of year.

“Conspicuous consumption of valuable goods is a means of reputability to the gentleman of leisure. As wealth accumulates on his hands, his own unaided effort will not avail to sufficiently put his opulence in evidence by this method. The aid of friends and competitors is therefore brought in by resorting to the giving of valuable presents and expensive feasts and entertainments.” (From The Theory of the Leisure Class, chapter 4.)

Yes, he was grim. This approach grabbed me when I was in my 20s. I thought he was an esthete. In fact, he was an assistant professor who’d grown up in Minnesota. And, he was right. It’s so easy right now to start throwing money at what ought to be love for our friends and relatives. Hold back, folks. Ask: What are the presents I have received that meant the most to me over the years? They usually aren’t the things that cost a lot of money. My mother still talks about the year I was a junior in college and, strapped for money and time, showed up with specialty magazines for each of my parents, my three brothers, and my sister. My presents brought down the house that year.

It was one pre-holiday season, many years ago when I was working in Philadelphia for an alternative paper, when I began thinking maybe too hard about materialism at Christmas. I wrote an essay for my paper that made me sound like a woman ready to move to a labor camp. My mother was taken aback. Sorry, Mom! Your Christmases are magical. I was just trying to get a grip on myself.