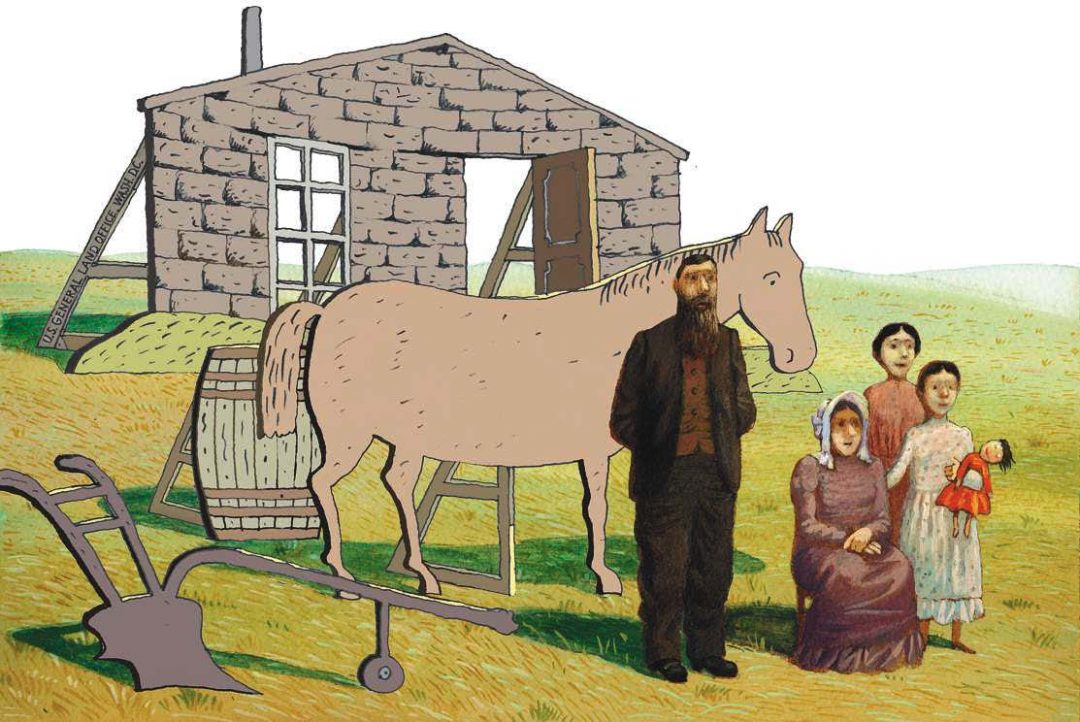

Illustration by Boris Kulikov for the Boston Globe

Was a beloved children’s series written as an anti-New Deal fable? The Wilder family papers suggest yes.

A FEW MONTHS AFTER the stock market crash, in the winter of 1930, Laura Ingalls Wilder sat at a small desk in Mansfield, Mo., and began writing down her life story in pencil.

She had rattled in wagons from cabin to sod house to shanty, slept to the howling of wolves, endured droughts, tornadoes, and blizzards,

cooked for teamsters, and ultimately married a man, Almanzo Wilder, with whom she’d done more of the same. Wilder was 63 when she started writing her memoirs, and she wasn’t an experienced writer: She had published little more than farm newspaper columns. But her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, 43, was a famous journalist, and she thought her mother’s story would sell.

“Once upon a time, years and years ago, Pa stopped the horses and the wagon theywere hauling away out on the prairie in Indian Territory,” Wilder

wrote in the earliest surviving draft, written in a notebook she labeled “Pioneer Girl No. 3.”

From her mother’s rough anecdotes, Lane typed and edited a manuscript called “Pioneer Girl,” but no magazine editor would buy it. So Lane spun one early section of the story into a children’s book: “Little House in the Big Woods,” followed two years later by a second book, “Little House on the Prairie.” Six more books would follow. The Little House books would come to rank among the best-selling children’s volumes ever written. With good cheer, Laura, her sisters Mary, Carrie, and Grace, and their parents, Ma and Pa, managed subsistence farms in harsh climates.

They started with nothing, put hands to the plows, and built lives out of strength and grit. From the publication of the first book in 1932, the series was immediately popular. And, at a time when President Franklin D. Roosevelt was introducing the major federal initiatives of the New Deal and Social Security as a way out of the Depression, the Little House books lulled children to sleep with the opposite message. The books placed self-reliance at the heart of the

American myth: If the pioneers wanted a farm they found one; if they needed food, they killed it or grew it; if they needed shelter, they built it. Although Wilder and Lane hid their partnership, preferring to keep Wilder in the spotlight as the homegrown author and heroine, scholars of children’s literature have long known that two women, not one, produced the Little House books. But less well understood has been how exactly they reshaped Wilder’s original story,

and why. Throughout the 1930s and early 1940s, as the Little House fans clamored for more, Wilder and Lane transformed the unpredictable hardships of the American frontier experience into a testament to the virtues of independence and courage. In Wilder’s original drafts, the family withstood the frontier with

their jaws set. After Lane revised them, the Ingallses managed the land and made it theirs, without leaning on anybody.

A close examination of the Wilder family papers suggests that Wilder’s daughter did far more than transcribe her mother’s pioneer tales: She shaped them and turned them from recollections into American fables, changing details where necessary to suit her version of the story. And if those fables sound like a perfect expression of Libertarian ideas—maximum personal freedom and limited need for the government—that’s no accident. Lane, and to an extent her mother, were affronted by taxes, the New Deal, and what they saw as Americans’ growing reliance on Washington. Eventually, as Lane became increasingly antigovernment, she would pursue her politics more openly, writing a strident political treatise and playing an important if little-known role inspiring the movement that eventually coalesced into the Libertarian Party.

Today, as Libertarian values move back into the mainstream of American politics, few citizens think to link them to a series of beloved childhood books. But the Little House books have done more than connect generations of Americans to the nation’s pioneer history: They have promoted a particular version of that history. The enduring appeal of the books tells us something about how deep the romance with self-reliance runs through American history, and the gaps between the Little House narrative and Wilder’s real life say a lot about the government help and interdependence that we sometimes find more convenient to leave out of that tale.

LAURA INGALLS WILDER was a farm girl born and bred who believed a farm was the one place where a man and woman could work in equal partnership. But her daughter, Rose, abandoned that life. She left the land at 17, found work as a telegrapher, then become a reporter in San Francisco. Eventually she traveled to Europe, writing for the American Red Cross. During the roaring 1920s, growing ever more successful as a writer of magazine fiction, she lived the high life and even had a big house and servants in Albania for a time. She made enough money to renovate the Wilders’ old farmhouse in Missouri—where

she then returned to live—and built her parents a retirement cottage nearby. In the farmhouse, she entertained cadres of writers from New York who

arrived by steam train. She hired a cook, housekeeper, and farm hands.

Unlike her parents and grandparents, Lane turned up her nose at manual labor, and there’s little evidence to suggest she felt any reverence for the hardscrabble people of the plains. In 1933, Lane sketched an outline, never finished, for a “big American novel.” One of the characters was the pioneer, whom she described as “a poor man, of obscure or debased birth, without ability to rise from the mass.” In a letter to her old boss in April 1929, six months before the stock market crash, she had written: “Personally, I believe what we need—what every social group needs—is a peasant class.”

Read the rest of my story that appeared in the Ideas section of the Boston Globe on August 11 at this link:

http://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/08/09/little-libertarians-prairie-…

About This Article

My writing workshop colleague Farah Stockman of the Boston Globe introduced me to Stephen Heuser, the Ideas section editor of the Globe. This article comes right out of working drafts of my book about Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane. I’m focusing on their secret writing partnership during the Depression and how they reshaped the pioneer myth, changing it from one of endurance by people with few options to one of courage and independence.