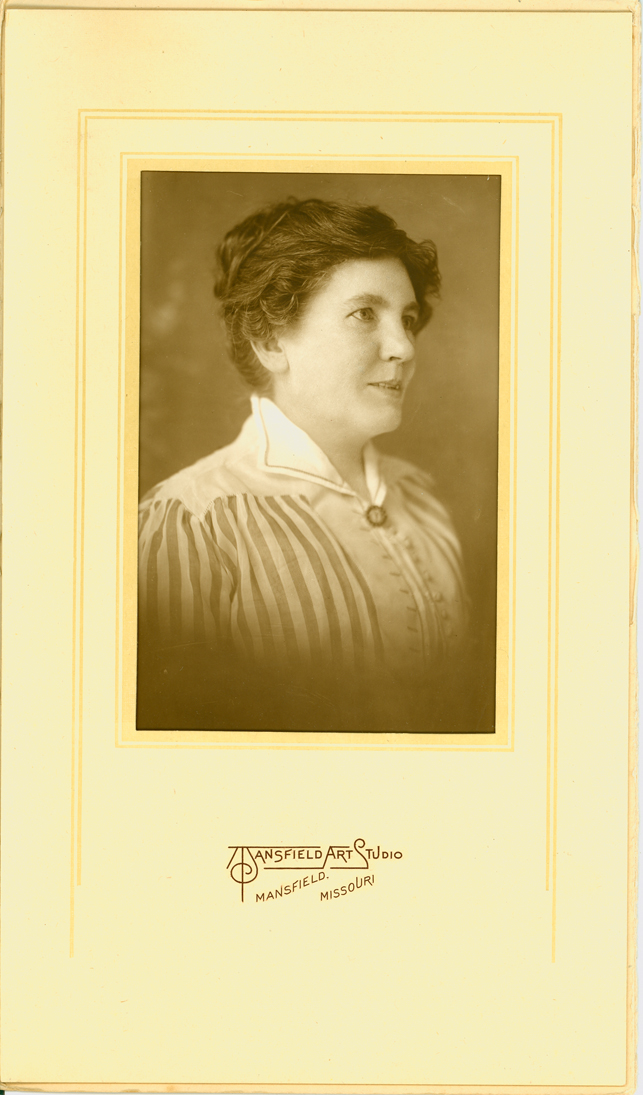

Laura Ingalls Wilder at about age 50, before she wrote the “Little House” books. Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

My heroine is Laura Ingalls Wilder. She’s not the woman I thought she was. Still a great woman, but a much different one than I thought.

As I work through the drafts of my book on the literary collaboration between Laura and her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, I realize that I am coming to know the real woman anew. The Laura I and millions of fans have loved is the free-spirited prairie girl. Laura the writer is also a stern mother, arguing and acting passive-aggressive with her editor daughter. She’s an intelligent but spottily educated farmer’s wife who understood theme and plot as only a thread of an idea running through pages.

Therefore, in her earliest drafts of the “Little House” books, she did not mold her stories to a larger point. Rose did that for her. But after the fifth book, By the Shores of Silver Lake, Rose, who by then had moved a thousand miles away from her mother, stopped doing that. Laura still mailed her the manuscripts of The Long Winter and a book she called Prairie Girl, but which turned into the last two books. Rose still “ran them through my typewriter” but had lost the energy to work with her mother. They were largely estranged.

Nowhere is the undisciplined ramble of Laura’s first drafts clearer than in the last one published, after both women had died. The First Four Years (named this by Rose’s heir) reads much like the previous book, These Happy Golden Years, only it leads to nothing. In the end, after crop failures, financial disaster, a baby’s death, and a house fire, they conclude that they’ll simply go on. That’s of course the strength of the pioneers in them, but in a written story, the ideas must all lead us somewhere. Laura knew this, and that’s why she sent her drafts to Rose. Rose knew this, and that’s why she continued to revise the drafts for Laura.

My heart aches when I page through this manuscript of The First Four Years. Rose wouldn’t touch this one.