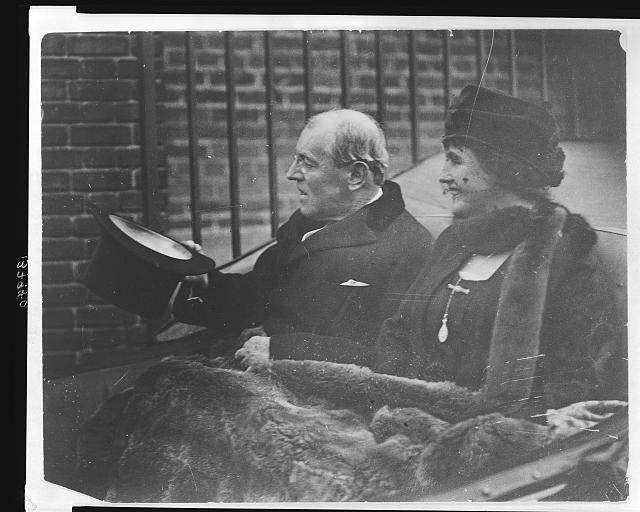

President Woodrow Wilson and his second wife, Edith, in 1922. Photo from Library of Congress

A 125-page biography in the Penguin Lives series blends storytelling and journalism in a clear, fast-paced overview of a complicated man, Woodrow Wilson. The novelist Louis Auchincloss synthesized many thousands of pages of reading and understanding. A writer who studies and uses the lessons in this book’s structure will find readers hanging on, putting off eating lunch. A few weeks ago an early reader of my next book paid me that kind of compliment: he’d stayed up too late reading my manuscript. In other words, he didn’t want to stop. Now, I hope everyone has that reaction. If they do, I owe writers like Mark Kramer (my teacher) and his book Three Farms, Gretel Ehrlich, Timothy Egan, Edward Abbey, and, especially, Louis Auchincloss in this little biography of Wilson.

He begins near the end of Wilson’s life, with a collapse from a small stroke inside a train that has just pulled into Wichita, Kansas, where a crowd waits. Auchincloss thus begins the story with Wilson’s frail health. He then builds the story of Wilson’s life around this moment of bodily collapse. “We shall see that there were always two Woodrow Wilsons,” he says on page 3 (page 3!), “and that the tragedy of his bad health understandably contributed to the lesser and not the greater of the two. This ambivalence in a man so admired confused many who observed him closely. I believe it confused himself.” This is one of a handful of times that Auchincloss inserts himself, “I,” into the story that runs and runs along like a spring stream. He makes a dramatic case that Wilson’s second wife, Edith, and the doctor, caused the failure of the League of Nations.

He returned from Paris in 1919 determined that a treaty calling for a League of Nations must pass. Secretary of State Lansing thought Wilson “imprisoned within his own certainties.” His temper boiled over; his opponents in Congress took advantage of that, perhaps, and drafted a new version of the treaty that would strongly preserve America’s right to stay out of future wars if it chose. Wilson said he’d already signed the treaty. Soon after, Wilson lay in bed, rarely talking to his colleagues except for a few minutes’ dim-lit interview, his left arm hidden under a blanket. Edith Wilson could have been running the country for a while there, in her husband’s last months in office. The doctor said she herself should weigh every request. Many a staffer conferred with the president through Mrs. Wilson’s words delivered through the narrow crack of the door to her husband’s bedroom.

Historians might disagree with Auchincloss’s take on things. And of course everyone is welcome to write his or her own book. Woodrow Wilson reminds writers that one good book sustains perhaps two or three big ideas. Decide what those ideas will be. Then write the story and give the readers a few handrails on which to steady themselves as they go.