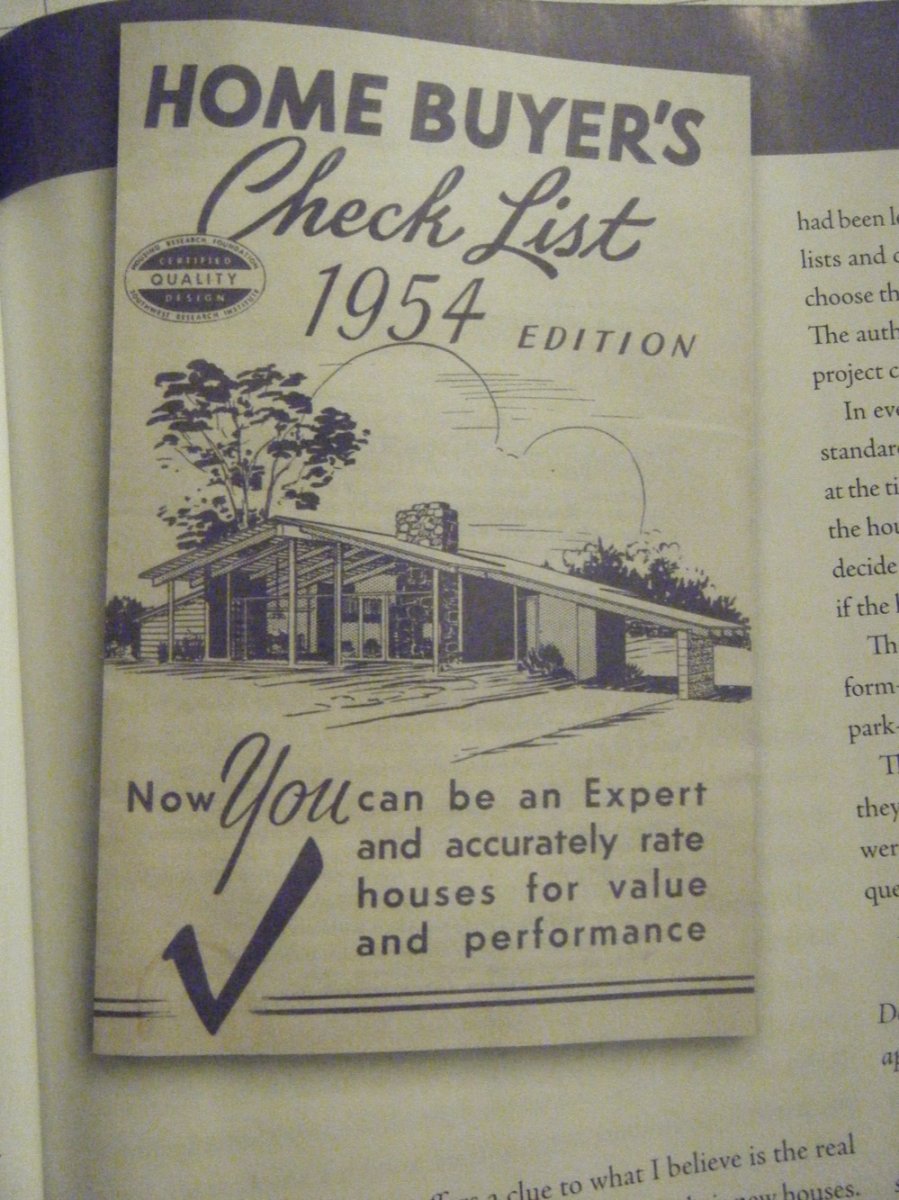

The pamphlet my husband found at the dump

written for New England Watershed

Attitudes toward housing in the 1950s—and now

Several years ago, I was assigned to write a newspaper article about a kitchen tour in Old Lyme, Connecticut. The best kitchen of the day was at the back of a charming stone house overlooking the marshes of the lower Connecticut River. You could stand at the granite countertop chopping vegetables while watching the sun play on the waving marsh grasses outside the giant window.

Enthusiastically, I said to the owner, “You must love cooking here!” and she responded, smiling, “Yes, I do.”

Later, someone in town told me that she never cooked, a fact that might have prepared me, as I stood in the owner’s kitchen, for what she showed me next. She beckoned past the gleaming restaurant stove to a closed door and said, “I don’t know if I should show you this, but come on in.”

We entered a long, windowless closet. On one wall was an upright piano with a scattering of music paper. This was her musician husband’s work station. Against the other wall was a desk covered with paperwork. This was where she did her bills and correspondence. We walked a little farther back to a work table and ironing board and a basket or two of laundry waiting to be folded. “We spend most of our time in here,” she told me.

Had I described this bunker in my kitchen-tour article, I might have unearthed something about how people don’t know how to relax in their showpiece houses. But I was a good soldier. I understood that my task in writing about the kitchen tour was to celebrate the possibility of “perfect” domestic spaces filled with light and beauty—whether people were actually using them or not.

When urban social critic Jane Jacobs died in April 2006, Americans began revisiting her sharp observations about modern urban renewal projects, with their impersonal buildings surrounded by empty space. She insisted that those attempts to make cities beautiful ignored the natural human attraction to small buildings and a jumble of activity. Jacobs’s views on cities penetrate well into the question: why are houses in both cities and the country getting larger, and why do they not seem to satisfy people?

“There is a quality even meaner than outright ugliness or disorder,” Jacobs wrote in The Death and Life of American Cities, “and this meaner quality is the dishonest mask of pretended order, achieved by ignoring or suppressing the real order that is struggling to exist and be served.”

That’s exactly what was going on inside the kitchen-tour showpiece house overlooking the Old Lyme marshes. The sterile beauty of the unused kitchen and living rooms suppressed the “real order” of the couple’s activities. The two were not willing to sully the “pretended order” of the gorgeous furniture and appliances in the airy rooms, so they retreated to their closet to live.

The work-space closet offers a clue to what I believe is the real truth: many people aren’t using most of the space in their new houses. Yet people think they want this space; they ask builders for it, and builders comply. New American houses in both cities and suburbs have been getting larger by the year since 1950. Then, the average new house in America measured 983 square feet. By 2005, the average had jumped to 2,433 square feet.

In 1950, 96 percent of houses had one and a half bathrooms or fewer. By 2004, 96 percent had two bathrooms or more. In 1950, 53 percent of houses had garages for two cars or more. (Statistics from the National Association of Home Builders.)

Advice on choosing a house—then and now

Since the first great suburban boom after World War II, Americans have shopped for new houses with checklists in hand. These qualities desired in their neighborhood and house drive their decisions to buy, and builders naturally try to give them what they want.

I recently came into possession of a 1954 pamphlet on how to pick the perfect house. Home Buyer’s Check List 1954 Edition: Now You Can Be an Expert and Accurately Rate Houses for Value and Performance had been left in a box in the landfill of our town dump. The pamphlet’s lists and checkboxes instructed home buyers, item by item, how to choose the right house in the burgeoning suburbs of the postwar era. The authors worked for the Southeast Research Institute under a project called the Housing Research Foundation.

In every list lies the assumption that you can insist on a certain standard, one that went well beyond what most people experienced at the time. The pamphlet said that home buyers should ask how close the house stood to others and how the streets lined up. They should decide if they liked the neighbors, how easy it was to park the car, and if the house was too different in appearance from the others.

The pamphlet tells buyers to give high scores to houses that conform—without matching each other exactly—and are situated in a park-like setting. Anything else would not do.

The section “The Neighborhood” asked buyers to score houses they were considering. If they answered “no” to any questions, they were advised to “score 0” on those questions. Here are some sample questions, with occasional advice in parentheses:

Is the neighborhood attractive?

Are the people you see the kind you would like to have as neighbors?

Do the streets curve occasionally? (Discourages through traffic and improves appearance.)

Do the houses seem crowded together? (If so, score 0.)

Are the houses so nearly identical that the effect is unpleasant? (If so, score 0.)

Are the houses so different that the result is a hodge-podge? (If so, score 0. In the effort to avoid identical repetition, builders sometimes go too far in the other direction.)

The pamphlet’s writers urged buyers to make a spot judgment of the neighborhood and its people. All city neighborhoods “score 0.” The houses must look different, and yet not so different that any one stands out too much. The effect the authors wanted could exist only in a specific kind of postwar suburb.

In the section “The Outside of the House,” they asked:

Is it simple? (That is, are there few materials, few breaks or projections in the walls and roof, few applied decorations.)

Does it imitate some style of the past, such as Cape Cod, Georgian, Spanish, etc.? (If so, score 0.)

Does it have a number of quaint or “cute” features, such as cupolas, bird houses, scalloped valances, lamp posts, ox-yokes, wagon wheels, fences that do not enclose anything; and shutters that do not shut? (If so, score 0.) You will tire of these very soon and wish that the builder had spent the money on better plumbing, say, or more insulation.

What house other than a modern ranch could be as simple as the Check List authors proscribed?

In the section “Inside the House,” the writers indicated that the kitchen should be partly open to the dining room but possible to close it off entirely for formal meals—people should not have to walk where the cooking went on. The counters must be long, with large areas for storage, hobbies and maintenance projects.

Americans still aspire to big houses with ample storage, far from neighbors, yet safe—secluded and cocooned.

I have always believed that the World War II generation was tired—of noise, stress, rationing and job shortages, of losing people too young. They deserved houses set in groves. What about future generations? What should be on a housing check list in 2006.

The National Association of Realtors offers, “Tips for Finding the Perfect Neighborhood.” They include:

Check out the school district.

Determine if the neighborhood is economically stable.

Determine how much you could make if you later sell your house.

See if homes are “tidy and well maintained” and if streets are quiet.

In “Your Property Wish List,” NAR asks:

What neighborhoods would you prefer?

What school systems do you want to be near?

What architectural style(s) of homes do you prefer?

How close do you need to be to… public transportation, schools, airport, expressway, neighborhood shopping…?

A chart from the NAR lists every aspect of the outdoors and indoors, room by room, offering two choices for each: “must have” or “would prefer.” (There is no column labeled “willing to do without.”) It looks like this:

Prioritize each of these options into MUST HAVE or WOULD PREFER:

Yard (at least _____)

Garage (size_____)

Patio/Deck

Pool

Bedrooms (number _____)

Bathrooms (number _____)

Family room

Formal living room

Formal dining room

Eat-in kitchen

Laundry room

Basement

Attic

Fireplace

Spa in bath

Air conditioning

Wall-to-wall carpet

Hardwood floors

View

Light (windows)

Shade

As someone who grew up in the Northeast in two suburban houses built in the 1950s, I appreciate quiet, tree-lined neighborhoods. I understand what my parents sought in their houses. My father had been raised in row houses in Trenton, New Jersey. He couldn’t wait to get some distance between his living room and the noises of other families. He relished his back yard for the buffer it offered.

My mother grew up in larger row houses in Philadelphia. As an adult in a split-level house, she chose a muted green carpet because, she said, the rug seemed to extend the beauty of the outdoors, viewed through the picture window, to the inside. It was true: our living room felt a little like a park. I get choked up thinking about my parents’ joy in these houses. They provided ample room for a child to spread out.

I was one of five children, and today the average family size in America is much smaller—and shrinking. The National Association of Home Builders reported this year that the average family size is now 2.5 people, down from three during the last three decades, while the average residence has expanded by 50 percent over that time.

Our yearning for expansive domestic spaces grows, and with it comes some parallel and stomach-turning trends. In April, Jeff Turrentine reported in the Washington Post that, 50 years ago, the average American kitchen measured about 80 square feet and the average American man weighed about 166 pounds. Now, the average American kitchen has extended to 225 square feet, and the average American man weighs about 191 pounds.

People are getting fatter as their kitchens do (or vice versa). This may be more symbolic than causal. People don’t cook as much as they used to. In the Old Lyme kitchen overlooking the marshes, food wasn’t the main object. The rise of gourmet take-out meals and the newest trend, meal-assembly stores, refute the idea that large kitchens are necessary to prepare food. But people do continue to want something—the idea that they could cook old-fashioned meals, perhaps.

In the winter-spring 2005 issue of the Journal of Industrial Ecology, Alex Wilson and Jessica Boehland quoted the designer and builder John Abrams of the South Mountain Company in West Tisbury, Massachusetts. Abrams says three factors drive the popularity of large houses:

“First, with less of a sense of community and public life in our culture, the home becomes a fortress which needs to contain everything we need, including multiple forms of entertainment, rather than basic shelter. Second, the building industry has been selling ‘big is better’ and the message has been heard; and third, diminishing craft and design generosity has resulted in sterile homes—people mistakenly think that what’s missing is grandeur: more space.”

Reached at his office, Abrams said that, despite these factors, the movement toward smaller, more distinctive houses is growing. He cites Sarah Susanka’s 1998 book, The Not So Big House, and two sequels designed to help people plan smaller dwellings. Hundreds of thousands of the books have sold. Abrams, who specializes in smaller houses, said that the interest in going smaller is “huge.”

When will the majority of new houses in America start shrinking? From 1978 to last year, the average square footage of new homes grew by nearly 40 percent. Now that aging baby boomers are beginning to build retirement houses, the expectation is that many of these will be smaller, says Steve Melvin, director of economic services at the National Association of Home Builders.

But the general new-house trend shows now sign of abatement. Even downsizing homebuilders have checklists of amenities. Melvin says that the NAHB surveyed 3,000 people looking to build new houses in 2003-04. The big items on their wish lists were more storage space and “quality items in the kitchen.” Outdoor fireplaces, higher ceilings and outdoor kitchens have also become popular desires.

This summer, Melvin says, the NAHB will survey architects about the houses of the future. “Everything they’re doing is based on consumer preferences,” he says, and what people want is more space to spread out. “You definitely don’t see ‘Ozzie and Harriet’ and two brothers rooming together in one room,” he says. “They’re going to have separate bedrooms, and the bedroom is going to be spectacular, and it’s going to be gender specific and it’s going to have bells and whistles until they go to high school.”

Since the days of the 1954 Home Buyer’s Check List, basic assumptions about how we want to live have risen. Melvin says some friends of his bought a new house recently and commented that they didn’t really need a microwave or garbage disposal. Air conditioning is a given today—it didn’t used to be.

Only fireplaces have declined in number. It’s a change in expectations. What we’re left wondering, though, is whether we know how to live with the things we think we want.

About This Article

This article was inspired by a pamphlet found at the Deep River, Connecticut, dump by Chris Woodside’s husband, Nat Eddy. This article first appeared in New England Watershed magazine’s June-July 2006 issue. Russell Powell was the editor. The magazine won an Utne Reader Independent Press Award for best new publication in 2006. It stopped publishing at the end of 2007.