Laura Ingalls Wilder was an American farmer and small-town farm journalist who rarely got involved in 20th-century politics. She was not an activist for the vote and only entered in politics in old age, when she ran for a paid local office — and lost.

Laura Ingalls Wilder was an American farmer and small-town farm journalist who rarely got involved in 20th-century politics. She was not an activist for the vote and only entered in politics in old age, when she ran for a paid local office — and lost.

And yet for decades, conservative Americans have held up her series, the Little House books, which includes Little House on the Prairie, as a Bible of libertarianism: true examples of American self-reliance and independent spirit. The nine children’s books about a hard-working pioneer family warned about the encroaching power of the state, and heralded the rise of the modern Republican party. They are fiction, of course, but based on Wilder’s real childhood.

Published in the throes of the Great Depression, the Little House books were powerful allegories opposing President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programmes, which provided unprecedented financial support to struggling Americans. They also illustrated a major shift in Republican ideology that took place in the Thirties, as the party sought to widen its appeal. It shed its reputation as the party of elite business owners, and instead began to emphasise the power of the individual.

In one of the scenes in The Long Winter, a storekeeper is overcharging starving residents of De Smet, South Dakota, who want to buy the last grain in town. A riot seems imminent until the hero of the books, Charles “Pa” Ingalls, speaks up. “This is a free country, and every man’s got a right to do as he pleases with his own property,” he tells the storekeeper. “Don’t forget that every one of us is free and independent, Loftus. This winter won’t last forever, and maybe you want to go on doing business after it’s over.”’

This impromptu speech is anachronistic: arguing about unregulated markets was a debate rooted in the Thirties, when this book was written, rather than the 1880s, when it was set. It hints at the secret lying at the heart of the Little House books: it was Wilder’s daughter and secret co-author, Rose Wilder Lane, who imbued the books with their political message.

Lane was one of the intellectual architects of the libertarian political movement in America: she was an influential free-market activist, writer, and acquaintance of the philosopher Ayn Rand. Her projection of her radical political views onto her mother’s pioneering childhood means that the series should be read as a double history: folk stories about the 1870s and 1880s woven through the vantage point of the Great Depression and the Second World War.

Pulsing through the books, meanwhile, are principles rooted in the Declaration of Independence. Thanks often to Lane’s revisions, characters occasionally quote that document, noting that they want to be “free and independent”. In Little Town on the Prairie, Pa takes Laura and her sister to the Fourth of July celebration in town. In Lane’s revision, Laura is transfixed by the reading of the Declaration of Independence and the singing of My Country Tis of Thee:

“The crowd was scattering away then, but Laura stood stock still. Suddenly she had a completely new thought. The Declaration and the Song came together in her mind, and she thought: God is America’s king. She thought: Americans won’t obey any king on earth. Americans are free. That means they have to obey their own consciences.”

This is why the books are so beloved by conservatives today: these libertarian views formed the basis of the modern Republican Party.

Yet the books purposefully understate the difficulty of the American pioneer experience. It was in fact a brutally hard life of crop failures, isolation, and disease. Although the Little House books preserved in accurate and lyrical detail many of the skills that small farmers practiced in the 19th century, Lane recast many scenes as optimistic takes on tragedy that did not reflect how the family actually responded. In On the Banks of Plum Creek, Pa announced during a horrible plague of the Rocky Mountain locust that ate crops for two years: “We won’t let a pesky crop of grasshoppers stop us.” The locusts did, in fact, lead to their financial ruin. Two years later, according to Little Town on the Prairie, the family resorted to eating the blackbirds that had destroyed their first corn crop in Dakota Territory. The family sings Sing a Song of Sixpence at the table. And why not show some upbeat pluck in a children’s book?

But Wilder cautioned her daughter that the family was not an optimistic group. The quality they relied on was stoicism, putting up with the bad that came. That’s very different from hope. “I wish I could explain to you about the stoicism of the people,” she wrote to Lane in 1938, when they were halfway through writing the series. “You know a person cannot live at a high pitch of emotion. The feelings become dulled by a natural, unconscious effort at self-preservation.” Wilder insisted that the Ingalls family had never reacted to anything emotionally.

The divergence between Wilder’s real-life story and the Little House narrative was also apparent from what they left out: crime and tragedy. Gone from the books were stories Laura had written in early drafts: the death of a baby brother, a mournful episode running a tavern that ended with the family fleeing late at night to avoid paying its debts. The hardships that did stay in the books shored up tenaciousness as a value, such as sister Mary Ingalls going blind as a teenager. Laura then had to step in to help her and support the family by teaching at several schools.

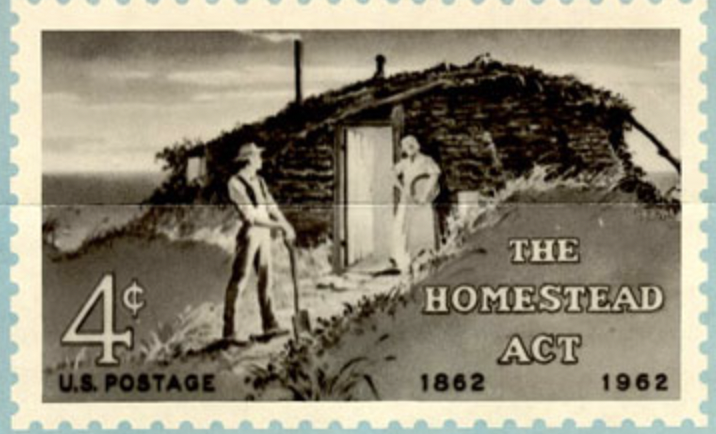

The books also downplayed the various ways the government helped the family, spinning a myth of self-reliance. Like many pioneer settlers, they were given a free homestead through the federal Homestead Act, which granted tracts the government had taken from American Indians. Then there was sister Mary’s state-paid college for the blind in Iowa. The stories only talk of Laura having to teach to pay for Mary’s college expenses — perhaps her clothes.

The stories continue to exert a kind of power on the American psyche. The books have sold more than 60 million copies and were taught in classrooms for many decades; the series remains part of homeschooling curricula. “Laura Ingalls Wilder is the quintessential American pioneer,” says Wilder expert William Anderson in the PBS American Masters documentary Laura Ingalls Wilder: Prairie to Page.

And Lane’s legacy can still be felt in the Republican party. Lane only wrote political articles after publishing the Little House books and her libertarian treatise The Discovery of Freedom. But she campaigned for limited government in the last years of her life. In the Sixties, she took under her ideological wing a young man in Connecticut; he was Roger Lea MacBride, who became a champion of libertarian thought and ran for president for the new Libertarian Party in 1976. Later, MacBride took the libertarian ideas with him as he migrated back to the Republican party’s Liberty Caucus.

Lane also donated funds to help businessman Robert LeFevre launch an institution for adults in Colorado called the Freedom School, which named a building after Lane. Two of the early students who studied free markets and limited government there were Charles and David Koch, who went on to become members of the Libertarian Party in the Seventies and Eighties. Later, they returned to the conservative branches of the Republican Party and became hugely influential by donating money to Republicans promising to support free-market concerns, including such notions as refuting the science of climate change.

The myth of the pioneers, embodied by Laura Ingalls Wilder, inspired many conservative American values today. They were seen as the kind of independent, self-reliant Americans that the Second Amendment was designed to protect. But even they would have struggled with some aspects of modern Republican policy — gun control in particular.

Certainly, the Ingalls family owned and used guns. In one scene in Little House in the Big Woods, Pa Ingalls trudges with his rifle through the snow of northern Wisconsin, checking animal traps. Rounding a large pine tree, he meets a black bear, standing on its hind legs clutching a dead pig. Pa aims his gun, kills the bear, and immediately runs home for the horses and sled to take the meat home. There, it resides in frozen form in a shed. Pa hacks off pieces with an axe at mealtimes.

Even the mythical Pa Ingalls would not have thought today’s Americans needed guns in most situations, especially the range of weapons available today. He preached to his daughters the necessity of restraint. “You wouldn’t shoot a little baby deer, would you, Pa?” says Laura. “‘No, never!’ he answered. ‘Nor its Ma, nor its Pa. No more hunting, now, till all the little wild animals have grown up. We’ll just have to do without fresh meat till fall.’”

When baby animals were roaming the forest, it was time to put the rifle away.

This article first appeared in unherd,com.