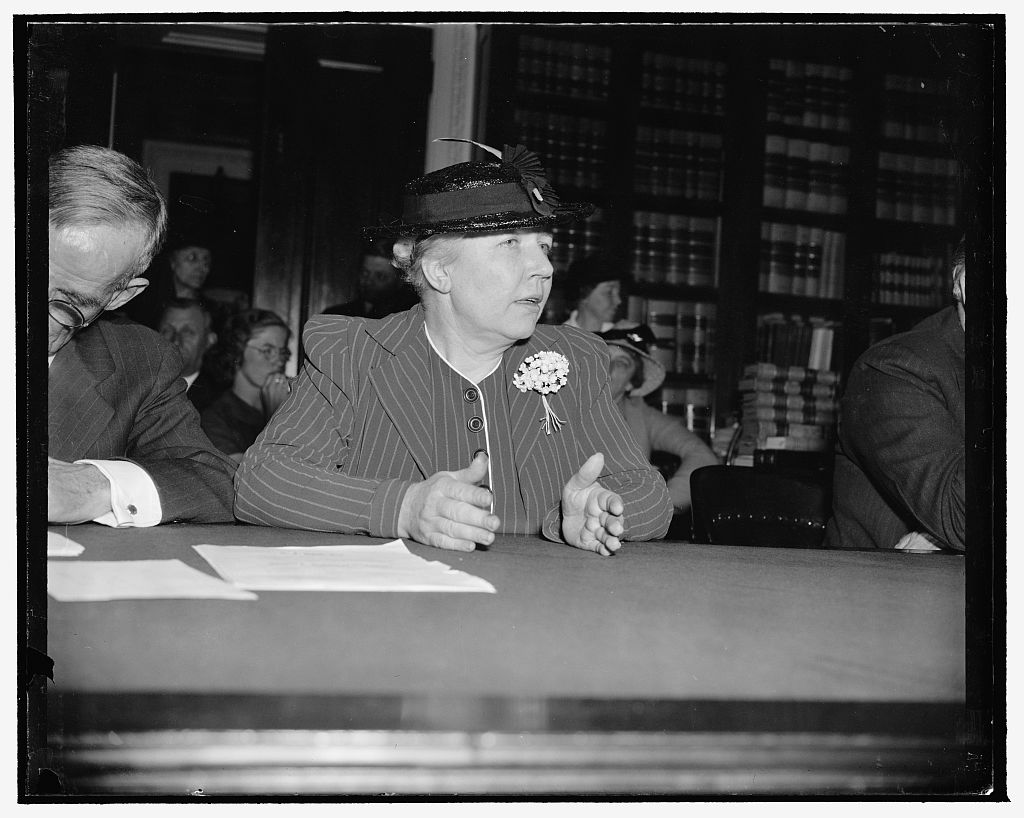

Rose Wilder Lane testifying in 1939 before Congress. She favored the Ludlow Amendment, which would have taken declaring war to a vote of the people. (Library of Congress photo)

Connecticut Explored, Fall 2010

Over the past several years, my pursuit of information about the “real” Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of the Little House series of children’s books (written from 1932 to 1943), has led me to restored houses, museums, courthouses, and libraries in Wisconsin, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, South Dakota, Missouri, New York, and Iowa. Yet even as I traveled to such far-flung places, I was living less than an hour’s drive from one of the most important locales in the author’s literary history: Danbury, Connecticut, where Wilder’s daughter Rose Wilder Lane moved halfway through their collaboration on the book series. From Danbury, Lane collaborated by mail with her mother on By the Shores of Silver Lake, The Long Winter, Little Town on the Prairie, and These Happy Golden Years.

Wilder visited Danbury just once, but her daughter, herself a writer, editor, and founder of the American Libertarian movement, lived there for 30 years and achieved lasting work on Wilder’s books there.

Lane moved to Danbury in 1938 to be nearer her writing circles in New York after a falling-out with her mother. Born in the Dakota Territory in 1886, she grew up helping her family struggle on the land there before her family moved to Florida and finally to the farm in Mansfield, Missouri. Rose escaped the farm at 17 to finish high school. Her varied career included a stint as an editor and writer at the San Francisco Bulletin and work in telegraphy, real estate, and fiction writing. She married in 1909, lost a son in childbirth, and divorced in 1918. She published one of the first biographys of Herbert Hoover, traveled the world, and lived twice in Albania.

Feeling a duty to strengthen ties with her parents, Rose returned to the Missouri farmhouse to live from 1928 to 1937. Around 1930, as the Depression deepened, the two hatched the idea of publishing Wilder’s life story. Lane guided and edited her mother’s work with both patience and resentment. Tense meetings and meals punctuated their work in the Missouri farmhouse. Lane built her parents a retirement cottage about half a mile away while she lived in the family home—suggesting a certain lack of coziness.

They had a falling out in 1938, possibly because Lane sublet the farmhouse to a couple her mother did not like when she took on a book project out of town. Soon after, Lane moved to New York, then to Danbury. The two didn’t see each other again until Almanzo Wilder, Lane’s father, died in 1949.

The break, and Lane’s move east, did not interrupt the collaboration on the Little House books. But Lane’s attitude about writing had changed. As a younger woman, she insisted her mother spend less time tending hens and more hours writing, under the belief that farming was a way to remain a servant to your most basic needs, while writing was a way to rise to a better standard of living. Now, in Danbury, Lane herself spent less time writing and more time returning to her farming roots—this time as a political statement. In protest of President Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, especially Social Security, during World War II, she nearly stopped writing, refused a ration card, and farmed and canned produce on her land. “New Deal Can’t Expect Much Help from Rose Wilder Lane,” announced a Danbury newspaper headline in 1938. Lane was quoted saying the strength of America was withering under government handouts. She felt compelled to prove how easily she could feed herself on an income she now kept as low as possible to avoid paying taxes. Laura was right there with Rose in believing people were too soft. People complaining about not having work during the 1930s made her sick, she once wrote Rose.

Lane executed her duties as Little House collaborator very quietly. Not even their editor at Harper & Brothers knew of Lane’s role. In fact, only a few people realized the extent of her involvement. Norma Lee Browning, a journalist who visited for long periods, said it was clear how much work Lane was doing to prepare books for publication, but she remained adamant that Lane was not the main author. Browning knew that Lane didn’t want to be known as anyone’s ghostwriter or collaborator, as Lane felt it would discredit her. While the Little Housebooks expressed her own political ideology of self-sufficiency (she wrote many of the segments that dealt with political themes), in doing this work, Lane was largely fulfilling some kind of psychic debt to her mother rather than, in her view, furthering her own career.

By the late 1930s, Lane had become cynical about American life. She wanted to slip Libertarian ideas into fiction but found no market for such politically charged stories. Free Land (1937), a story about homesteaders much like her parents and grandparents and one of her best-received novels, was the last fiction published under her own name.

Lane in fact still had a lively imagination, and she prodded her mother to add details to the Little House books that brought alive flatly-told memories of her childhood. The few marked-up book drafts that survive, with notations by both Lane and Wilder, show how each woman contributed. This is especially true for the drafts honed during the Danbury years. The paucity of extant drafts, though, and the fact that Lane, a lifelong letter writer, curtailed her correspondence with her mother after their rift and did not save letters after 1938, makes the job of unraveling their work methods detective work.

The family business served both women well financially throughout their later years. Wilder assigned 10 percent of the royalties to her daughter a few years before she died, and Lane inherited the rights to the books. Lane died in Danbury in 1968.

These days, diehard Little House fans sometimes drive past the privately owned 23 King Street house, but aside from a slim folder of tired photocopies of press clippings and other ephemera in the public library, Danbury has little to show for its role in the Little House books. By contrast, in the restored farmhouse in Missouri, tour guides discuss Wilder’s drafting methods, using pencil on lined yellow paper tablets before sending them to her daughter in Connecticut for revision and editing. In Danbury, as Lane worked over stories about homesteading in Dakota, she was growing and eating vegetables from her Connecticut land. It was here where the other half of the literary story took place and where Rose, personally, came full circle back to the farm.

Wilder’s and Lane’s decision to conceal their collaboration runs counter to the values they taught readers in the Little House books, in which Laura famously could not tell a lie. We who as children clung to the themes of the Little House books learned from them to love wild places, to appreciate the animals and Native Americans that once inhabited them, that hard work for good causes matters, and, above all, that we should live with integrity and joy no matter what troubles come. And those themes endure, inspiring a television series that ran from 1974 to 1983, an animated series (1975), two made-for-television movies (2000, 2001), a television mini-series (2005), and a stage musical (2008) that began a national tour last fall with Melissa Gilbert (who played Laura in the original TV series) playing Ma.

The women’s deception also robbed Connecticut and Danbury of their place in the literary history of this important book series about the frontier. I am trying to correct the record.

About This Article

I am working on a book about my quest to know how Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane collaborated on the Little House books during the 1930s and early 1940s. This article appeared (with interesting photos) in Connecticut Explored, Volume 8 No. 4 in Fall 2010.