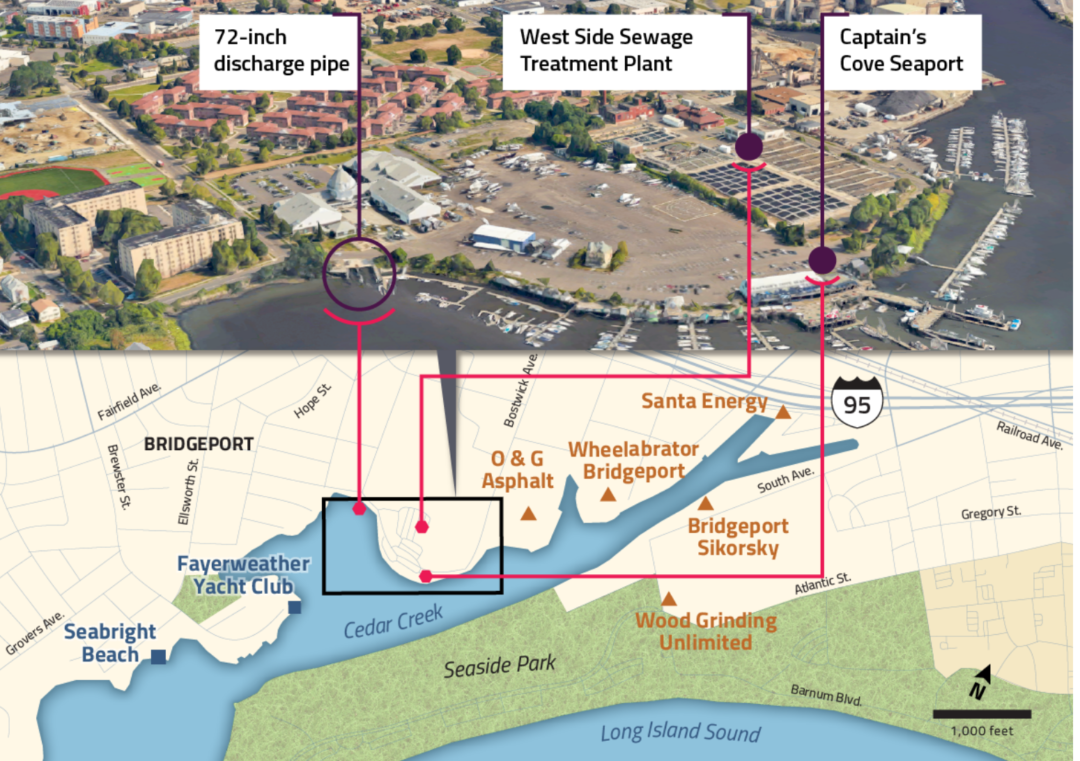

On the west and east sides of narrow Black Rock Harbor in western Bridgeport, industry, school, recreation and sewage treatment converge.

At the most inland tip are Santa Energy’s oil tanks. On the east side stretch asphalt runways at Pratt & Whitney’s test airport and a city landfill. On the west side stand O & G Industries sand and stone yard, an empty industrial building, a city landfill, a trash-to-energy plant, the regional aquaculture high school, a seaport, shops, a restaurant and sailing teams’ docks.

Last on this list is the Bridgeport West Side Water Pollution Control Facility, the city’s largest sewage treatment plant, which began work this year on a 20-year plan to correct chronic overflows.

All those buildings lie at the end of Bostwick Avenue, near the constant hum of I-95, a short distance from Seaside Park and

within view of a historic lighthouse and beautifully restored park called St. Mary’s by the Sea.

Sewage filters and breaks down at the West Side plant. The treated effluent pours through a 72-inch discharge pipe into Black Rock Harbor. Several times a year, stormwater mixed with sewage overwhelms the system of pipes leading to the plant. Then untreated sewage and rain diverts directly into the harbor through combined sewer overflow (CSO) pipes. Although the city has shut down some of its CSO pipes, 30 of them still are active, including the five in the Black Rock area.

Storms also regularly threaten the plant itself. Instead of flooding, the plant will speed that waste through a partial treatment called a plant bypass. Waste also bypasses treatment when equipment fails. Like the CSOs, the bypasses are legal and will remain so for decades.

The Legal Overflows

Every 10 days, on average, a sewage discharge flows into the harbor, according to July 2014-July 2019 data from DEEP. During that time span, CSO pipes in the Black Rock area discharged 99 times, and the West Side plant bypassed waste 85 times. CSO overflows were

estimated between 100,000 gallons and 500,000 gallons. Bypasses ranged from 1 million to 16 million gallons each.

Of the five pipes in Black Rock reported overflows include:

• One at Admiral and Harbor Streets, at Santa Energy, which has overflowed 26 times since 2014.

• A CSO at St. Stephen’s Road and Anthony Street—the location of the Bridgeport Regional Vocational Aquaculture School—which has overflowed 22 times.

• The CSO nearest the neighborhood beach, Seabright Beach, sends untreated waste off Brewster Street and Seabright Street, overflowing four times in late October 2017.

The 85 bypasses of partially treated sewage over the last five years—varying from 1 million gallons to 16 million gallons—discharged from the plaint’s main pipe below the Captain’s Cove Seaport office and next to its restaurant deck.

Reports of bypasses from 2019 include:

• Between April 26 at 4:40 p.m. and April 27 at 3:45 a.m., nearly 12 million gallons

• July 12 between 1:25 and 4:15 a.m., 11 million gallons

• Between July 17 at 5:50 p.m. and July 18 at 2 a.m., 11 million gallons

• Between July 22 at 6:30 p.m. and July 23 at 1:30 a.m., nearly 10 million gallons

Lauren McBennett Mappa has been the city’s water pollution control authority manager since January. She maintains that during heavy rainstorms, CSO pipes can overflow, but that the raw sewage being released is “very diluted,” and that it happens rarely.

The Orders

The state issued two orders to the city to correct its sewage overflow problems. Those orders cite violations of the federal discharge permit, issued through the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES).

Bridgeport’s required long-term control plan is designed to bring its sewage treatment into compliance with federal laws. By Nov. 30, 2020, the city must submit a report to the state detailing a schedule for completing upgrades to the plant. By May 31, 2022, “100% design plans shall be submitted” to the state. Construction on the upgrades must begin 4½ years from the date of the order, or September 2023, and must be finished by September 2026. The city and DEEP spent six years negotiating this plan, which requires new sludge storage tanks, odor control units and dryers. DEEP said chlorination and dichlorination of wastewater should have been automated a decade ago. The project is estimated to cost hundreds of millions of dollars to complete.

Those who work or relax near the plant’s discharge pipe, and near the five combined sewer overflow pipes that empty into this harbor, describe ugly-looking waste coming from the West Side plant at 205 Bostwick Ave. even on days when it is not raining.

Just ask Gail Robinson, who sells local real estate. Several years ago, she took a potential buyer to visit the open-air restaurant deck of Captain’s Cove Seaport. They stood admiring the view over the harbor. Then Robinson heard a gushing noise, and an ugly brown discharge rushed into the water just below her and her client. “I lost the sale,” said Robinson, who later founded the Ash Creek Conservation Association to advocate for clean water in that tributary of Black Rock Harbor.

Captain’s Cove Seaport manager Bruce Williams’ office overlooks the West Side’s discharge pipe. Often the discharge looks like chocolate mousse, he said. “There’s particle matter in that outflow. It settles and settles and settles, covering the bottom with a brown slurry a foot thick.”

Problems Persist In Other Cities

Sewage problems aren’t unique to Bridgeport. The problem persists in three other Connecticut cities: New Haven, Hartford, and Norwich. “It went from 13 cities to four remaining,” said Jennifer Perry, assistant director of infrastructure management in the water bureau of DEEP. “We’ve been working with [all four] for a pretty extended period of time.”

In Hartford, a $300 million project to store untreated sewage underground during storms is under construction. New Haven’s 80-year-old sewage plant—also serving East Haven, Hamden, and Woodbridge—overflows regularly. A 2009 consent order dictated plant upgrades, separating storm and sewage pipes, and bioswales. The predicted completion date is 2036.

By permit—until they fix the problems over the next few decades—these cities may divert raw sewage mixed with rainwater directly into rivers, inlets and Long Island Sound.

Anyone spending time in Black Rock, smelling the plant and seeing the discharges and overflows, might ask: Why in an age of robots and space travel can’t society treat its own human waste without polluting its beloved waterways in a time frame faster than over 20 years?

Part of the reason is that the work involves undoing a century-old infrastructure in the state’s largest city, costing hundreds of millions of dollars. Perry said Bridgeport had resisted separating sewer from stormwater pipes because it costs so much. But the city has begun separating some of the pipes. For other areas, its plan is to build underground storage tanks that would hold waste during storms.

The city itself admits its sewage treatment plants fail. In a pamphlet Bridgeport distributes, it says its two plants don’t always properly operate, can’t handle flow from common storms and fail to meet the federal standard of “nine minimum controls” that include a ban on discharging waste on days when it isn’t raining.

Perry said she’s not sure people realize what happens in Bridgeport when it rains. “We as an agency talk about it, but I’m not sure many people pay that much attention,” she said. “It happens when it’s raining and no one’s outside.”

Since 2012, by law, the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection records sewage outflows on maps. You can view the maps here.

Coming tomorrow Part 3: Black Rock area residents, including high school students, spent the spring and summer cruising the harbor and Long Island Sound gathering water samples for testing. They’re part of the Long Island Sound Unified Water Study, and like many living and working in the area they’re tired of the smelly, brown-slick water and beaches closed to swimming.

This project was supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists – Fund for Environmental Journalism.