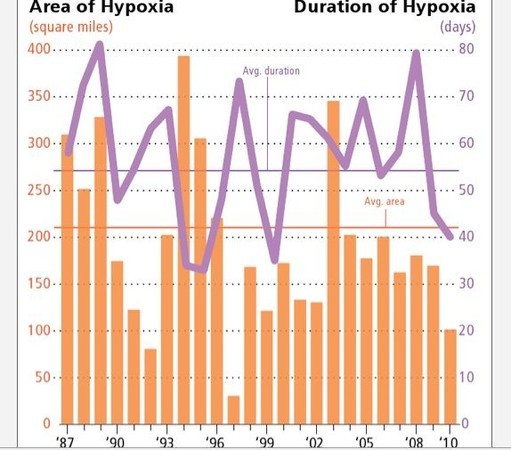

Orange bars mark hypoxia area; purple line marks duration. Long Island Sound Study

Patch.com

It is a killing combination: Connecticut’s developed coast bumps up against Long Island Sound, a quiet body of water with few exit points to the open ocean. Each summer, a dead zone forms at the western end. Oxygen levels in this 101-square-mile area kill marine life and acts as a sign of too much nitrogen entering the water.

Is the eastern stretch of the Sound exempt from the problems nitrogen causes? No. At the eastern end, the water is deeper and mixes more readily with fresh ocean water, but there the Sound still takes on the effluent and runoff of millions of people. How the Sound handles civilization’s onslaughts is different at either end.

“What happens in the western Sound, the consequence of too much fertilizer in the Sound is hypoxia,” said Mark Tedesco, who directs the Long Island Sound office of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “In the eastern Sound it’s not hypoxia, but loss of eelgrass.”

Eelgrass, which roots underwater along the coast, grows only in the eastern Sound, but historically it grew throughout the Sound. Eelgrass is sensitive to contamination, so when it struggles or disappears, that’s one of the earlier signs of something wrong in the water.

And when it recovers, as it seems to be doing in some areas, that’s one sign of improving water quality. Eelgrass covered more acreage (1,980 acres) in the latest detailed survey, in 2009, than in 2006 (1,905 acres) or 2002 (1,595 acres). New beds of eelgrass showed up on the south side of Fishers Island, offshore of Groton and New London, in the latest survey.

Eelgrass beds also grow in Niantic Bay (212 acres), Mystic Harbor (162 acres), Goshen Cove (124 acres), and Rocky Neck State Park (103 acres).

Eelgrass beds provide habitat and food for many marine animals. In the 1930s, a fungal disease almost wiped out the plant. Since the 1980s, excess nitrogen from sewage treatment and other water pollution have stressed and reduced its reach.

About that dead zone

The dead zone at the western end causes other problems for the eastern waters of the Sound. The dead zone forms when high amounts of nitrogen from sewage treatment, air emissions, and fertilizers pour into that warm, shallow (roughly 60 feet deep) bathtub that is the western Sound. The Sound is deeper (325 feet deep) off New London, at the area called the Race.

The nitrogen (400 times higher than it would be naturally) feeds big blooms of microscopic plants at the surface. As these plants, and the waste from animals that eat them, decay and fall to the bottom, oxygen at the bottom depletes. This is a problem in the summer because the water tends to sit in layers, with warm water stuck at the top and not enough mixing of oxygenated water.

The result is areas with hypoxia, meaning the water has less than 3 milligrams per liter of oxygen. Fish and creatures either leave, sicken, or die.

Recent data show that the dead zone measures about 101 square miles and lasts for about 40 days each summer. And this is an improvement over the running average of about 195 square miles over the last quarter-century.

The officials and scientists from state and federal agencies who run the Long Island Sound Study reported that the dead zone was below the quarter-century average for 11 out of the last 15 years. Last year’s 40-day period of hypoxia was the fourth shortest since measurements began in 1987.

Dozens of cities and towns in New York and Connecticut have worked to upgrade sewage plants under agreements that took years to put in place. These upgrades cost millions of dollars and are designed to remove some nitrogen from sewage effluent.

Tedesco of the EPA said it isn’t time for the Long Island Sound Study to close up shop. The entire Sound suffers from this syndrome.

“One thing to keep in mind is fish swim,” he said. “A fish you want to catch in the eastern Sound may be spending time in the western Sound. Bait fish that spend time in the western Sound may be part of the food chain for all of the Sound.”

Research now going on will attempt to connect wind speeds and directions to dead zone formation. The work isn’t done, but Tedesco said a wind out of the northeast, the kind that storms bring, mixes the Sound water, reducing the area of hypoxia. He said, “Years where the wind directions are more from the southwest will tend to have more severe hypoxia.”

Rethinking the lawn

Tedesco noted that Connecticut’s agricultural runoff is small, unlike areas around the Gulf of Mexico, where the dead zone approaches 8,000 square miles each year. Another huge dead zone is in Chesapeake Bay. The U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy has made dealing with this a priority.

But fertilizers applied to home lawns and gardens do contribute a portion of the nitrogen. “It’s a component,” Tedesco said. “We certainly encourage people to reduce the applications of the fertilizers.”

For more information

Long Island Sound Study

http://longislandsoundstudy.net/

About This Article

This was one of a series of weekly columns I wrote for eight patch.com sites in southeastern Connecticut.