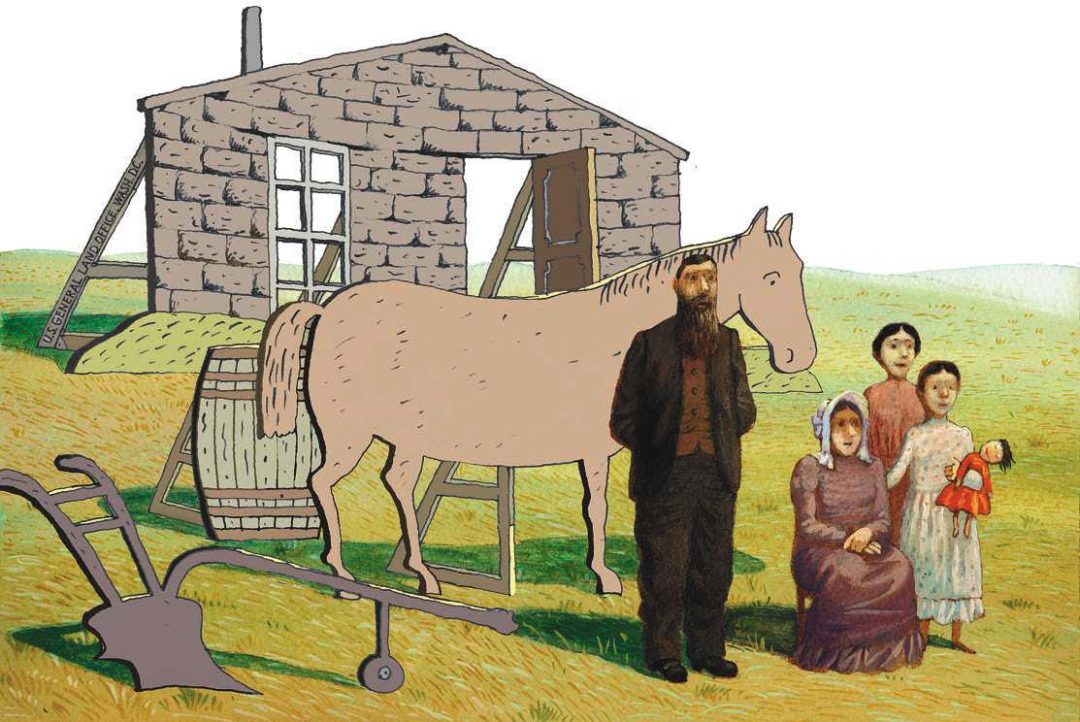

Illustration by Boris Kulikov for the Boston Globe

The Boston Globe, August 11, 2013

A few months after the stock market crash, in the winter of 1930, Laura Ingalls Wilder sat at a small desk in Mansfield, Mo., and began writing down her life story in pencil. She had rattled in wagons from cabin to sod house to shanty, slept to the howling of wolves, endured droughts, tornadoes, and blizzards, cooked for teamsters, and ultimately married a man, Almanzo Wilder, with whom she’d done more of the same. Wilder was 63 when she started writing down her life, and she wasn’t an experienced writer: She had published little more than farm newspaper columns. But her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, 43, was a famous journalist, and she thought her mother’s story would sell.

“Once upon a time, years and years ago, Pa stopped the horses and the wagon they were hauling away out on the prairie in Indian Territory,” Wilder wrote in the earliest surviving draft, written in a notebook she labeled “Pioneer Girl No. 3.”

From her mother’s rough anecdotes, Lane typed and edited a manuscript called “Pioneer Girl,” but no magazine editor would buy it. So Lane spun one early section of the story into a children’s book: “Little House in the Big Woods,” followed two years later by a second book, “Little House on the Prairie.” Six more books would follow. The Little House books would come to rank among the best-selling children’s volumes ever written. Laura, her sisters Mary, Carrie, and Grace, and their parents, Ma and Pa, managed subsistence farms in harsh climates with good cheer. They started with nothing, put hands to the plows, and built lives out of strength and grit.

From the publication of the first book in 1932, the series was immediately popular. And, at a time when President Franklin D. Roosevelt was introducing the major federal initiatives of the New Deal and Social Security as a way out of the Depression, the Little House books lulled children to sleep with the opposite message. The books placed self-reliance at the heart of the American myth: If the pioneers wanted a farm, they found one; if they needed food, they killed it or grew it; if they needed shelter, they built it.

Although Wilder and Lane hid their partnership, preferring to keep Wilder in the spotlight as the homegrown author and heroine, scholars of children’s literature have long known that two women, not one, produced the Little House books. But less well understood has been how exactly they reshaped Wilder’s original story, and why. Throughout the 1930s and early 1940s, as the Little House fans clamored for more, Wilder and Lane transformed the unpredictable hardships of the American frontier experience into a testament to the virtues of independence and courage. In Wilder’s original drafts, the family withstood the frontier with their jaws set. After Lane revised them, the Ingallses managed the land and made it theirs, without leaning on anybody.

A close examination of the Wilder family papers suggests that Wilder’s daughter did far more than transcribe her mother’s pioneer tales: She shaped them and turned them from recollections into American fables, changing details where necessary to suit her version of the story. And if those fables sound like a perfect expression of libertarian ideas—maximum personal freedom and limited need for the government—that’s no accident. Lane, and to an extent her mother, were affronted by taxes, the New Deal, and what they saw as Americans’ growing reliance on Washington. Eventually, as Lane became increasingly antigovernment, she would pursue her politics more openly, writing a strident political treatise and playing an important if little-known role inspiring the movement that eventually coalesced into the Libertarian Party.

Today, as Libertarian values move back into the mainstream of American politics, few citizens think to link them to a series of beloved childhood books. But the Little House books have done more than connect generations of Americans to the nation’s pioneer history: They have promoted a particular version of that history. The enduring appeal of the books tells us something about how deep the romance with self-reliance runs through American history, and the gaps between the Little House narrative and Wilders’ real life say a lot about the government help and interdependence that some of us sometimes find more convenient to leave out of that tale.

—

Laura Ingalls Wilder was a farm girl born and bred who believed a farm was the one place where a man and woman could work in equal partnership. But her daughter, Rose, abandoned that life. She left the land at 17, found work as a telegrapher, then become a reporter in San Francisco. Eventually she traveled to Europe, writing for the American Red Cross. During the roaring 1920s, growing ever more successful as a writer of magazine fiction, she lived the high life and even had a big house and servants in Albania for a time. She made enough money to renovate the Wilders’ old farmhouse in Missouri—where she then returned to live—and built her parents a retirement cottage nearby. In the farmhouse, she entertained cadres of writers from New York who arrived by steam train. She hired a cook, housekeeper, and farm hands.

Unlike her parents and grandparents, Lane turned her nose up at manual labor, and there’s little evidence to suggest she felt any reverence for the hardscrabble people of the plains. In 1933, Lane sketched an outline, never finished, for a “big American novel.” One of the characters was the pioneer, whom she described as “a poor man, of obscure or debased birth, without ability to rise from the mass.” In a letter to her old boss in April 1929, six months before the stock market crash, she had written: “Personally, I believe what we need—what every social group needs—is a peasant class.”

When Black Tuesday did come, the Wilder-Lane households began a painful two-year downslide, as Lane’s savings deflated from $20,000 to almost nothing. Magazine work almost dried up. Wilder, too, lost some money but, characteristically, scraped together savings and paid off the farm. Lane fretted about money, missed rent payments to her parents, borrowed thousands from friends, and continued to call herself the head of the household. She also began to consider other possible writing projects.

For a decade already Lane had milked various snippets from her parents’ lives for short stories. Now she saw an opportunity for her mother. Pioneer struggles could eerily mirror the struggles of the Great Depression, and Lane thought Americans were ready to hear about covered-wagon childhoods. After magazines rejected Wilder’s real-life account, Lane began reworking some of the memoir into what would become the first children’s book, “Little House in the Big Woods.”

Published in 1932 by Harper & Brothers, the book was praised by book critics for its honesty and caught the interest of readers nationwide. The Junior Literary Guild, a national book club, paid them an additional fee to print its own run. The income crisis at the Wilders’ ended. In the shadow of the crash, tales of overcoming great adversity resonated, and the editors wanted more.

Wilder and Lane responded with their now-famous sequels. From the start, there was tension between their approaches. Wilder argued for strict accuracy, while Lane, the seasoned commercial writer, injected made-up dialogue, took out stories about criminals and murder, and—most significantly—recast the stoic, sometimes confused pioneers as optimistic, capable people who achieved success without any government help.

Laura Ingalls Wilder never got used to Lane’s heavy rewrites, but the evidence suggests that on the main approach, playing up toughness in adversity, she agreed with her daughter. Both women believed fervently that the nation in the depths of the Depression had become too soft. In 1937, Wilder wrote Lane that people’s complaints about having no jobs made her sick. (“People drive me wild,” she wrote. “They as a whole are getting just what they deserve.”)

The early books celebrated Laura’s early childhood in a cozy log cabin in Wisconsin. They celebrated Pa Ingalls’s storytelling abilities and described in gripping detail how backwoods and prairie farmers took care of themselves—hunted, butchered, cooked, built, and made things like soap and bullets—in the 1860s and 1870s. The third book, “Farmer Boy,” was about Wilder’s husband Almanzo’s life on a New York State farm. In the fourth book, “On the Banks of Plum Creek,” the Ingalls family relocated to Minnesota (the locale of the TV show), where they built a house and became wheat farmers despite a grasshopper plague.

In shaping the memoirs into novels, Lane consistently left out the kinds of setbacks and behavior that cast doubt on the pioneer enterprise; the family’s story became a testament to the possibilities of self-sufficiency rather than its limitations. The last four books—which tell the story of the Ingalls family’s attempt to homestead in the future state of South Dakota—are particularly fired by libertarian themes.

Comparing Wilder’s original memoirs to the contents of the published books, it’s possible to see a pattern of strategic omissions and additions. In the fifth book, for example, “By the Shores of Silver Lake,” Laura promises to become a teacher to pay for her older sister Mary to attend a college for the blind. Wilder’s own account of her life reveals that although Wilder’s sister did attend a college for the blind, in reality it was the government of Dakota Territory—and not the family’s hard work—that covered the bills.

The next book, “The Long Winter,” stops for a moment of free-market speechifying almost certainly added by Lane. When a storekeeper tries to overcharge starving neighbors who want to buy the last stock of wheat available, a riot seems imminent until the character based on Wilder’s father, Pa, Charles Ingalls, brings him into line: “This is a free country and every man’s got a right to do as he pleases with his own property….Don’t forget that every one of us is free and independent, Loftus. This winter won’t last forever and maybe you want to go on doing business after it’s over.” It’s an appealing, if perhaps wishful, distillation of the idea that a free market can regulate itself perfectly well. Wilder rarely wrote extended dialogue in her own recollections, the manuscripts show; her daughter most likely invented this long exchange.

The Little House books barely mention the obvious, which is that the impoverished Ingallses never could have gone to Dakota Territory without a government grant: Like most pioneers, their livelihoods relied on the federal Homestead Act, which gave settlers 160 acres for the cost of a $14 filing fee—one of the largest acts of federal largesse in US history.

Wilder’s memoirs offer a picture of the costs and risks of isolation that never made it into the book series: A baby brother who died at 9 months. A miserable year working and living in an Iowa tavern. A pair of innkeepers who murdered guests and buried them out back. Another pioneer couple who boarded with them during the Long Winter whose attitudes were far more whining than stoic.

Perhaps the most telling omission is the book that almost never was. Wilder wrote one final volume, never revised by Lane, and not published until after they’d both died. “The First Four Years,” the ninth book, told of the drought that led to the failure of the Wilders’ first homestead after they were married in 1885. No one is sure why Lane did not revise that book, but it’s no stretch to imagine that she found herself at a loss to mold its dire underlying story—struggling, borrowing more and more money, losing the homestead anyway—into another celebration of self-sufficiency.

As Lane redrafted the last four of the original Little House books between 1937 and 1943, her extensive correspondence reveals, she was growing increasingly antigovernment in her personal views. She cut back her income specifically to avoid paying taxes; during World War II, Lane refused a ration card and retreated full time to her newly acquired 3-acre farm in Danbury, Conn., where she canned her own beans, beets, squash, and green-applesauce.

Throughout the early years of the Little House series, she had also continued to write fiction of her own. But Lane’s last novel, “Free Land,” about homesteading, published to great fanfare in 1938, had exhausted her. Her next effort, in 1939, the short story “Forgotten Man,” headed into what was becoming unpopular territory: It was an anti-New Deal story about a coal mine put out of business by government fees. The editors of the Saturday Evening Post rejected it for publication, calling it propaganda.

Once, in 1943, Lane was so outraged by a radio broadcast about Social Security that she penned an angry postcard comparing such programs to Nazi policies. (Someone sent it to the FBI, which dispatched a state trooper to her farm.) In 1944, the year after the last Little House book came out, newspaper reporter Helen L. Worden interviewed Lane, writing that Lane had “taken to the storm cellar until the Roosevelt administration blows over.” Lane had stopped writing her own novels, she said, “because I don’t want to contribute to the New Deal.”

She began to attend meetings against communism. She exchanged letters at the time with other conservative thinkers, including Isabel Paterson, H.L. Mencken, George Schuyler, and Clare Booth Luce. According to a 1990 biography of Lane by William Holtz, Lane socialized with Ayn Rand at her Danbury home and admired her writing, but found her elitist and irrational.

Just after World War II, an editor Lane had worked with introduced her to his 14-year-old son, Roger Lea MacBride. That began a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives. As a teenager, MacBride learned antitax principles at Lane’s knee in Danbury. Later, she enlisted him to help her revise a book that she intended as an explicit argument against big government, “The Discovery of Freedom.” It was published in 1943, and although it languished in obscurity for decades, Libertarian thinkers consider it a treatise that helped the party rise out of the strong anti-Communist movement of the time.

MacBride became Lane’s lawyer, agent, and her sole heir. Wilder, now a widow, remained on her Missouri farm, answering thousands of fans’ letters each year but rarely venturing out. In 1949 she instructed their agent to assign 10 percent of the Little House royalties to Lane. Lane made regular winter visits to Wilder until the pioneer author’s death at 90 in 1957. Lane, by then a rich woman doing little writing, started living most of the year in Texas. She died unexpectedly in her sleep in Danbury, the night before she had intended to leave on a world tour.

MacBride eventually went on to help form the Libertarian Party, and he ran on its presidential ticket in 1976. Lane’s thinking on limited government had from the beginning influenced a relatively small group of people; most writers of the era called Ayn Rand the “mother of the Libertarian party.” But MacBride believed that Lane was more important. In 1984 he wrote in an introduction that Lane’s political opus, “The Discovery of Freedom,” was “the seminal force creating the current wide trend toward individualistic views in America.”

—

MacBride failed as a politician, but he succeeded at managing Lane’s estate. Lane had been divorced since 1918; her only child had died at birth. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s will had specified that when her daughter died, the valuable book rights should go to the tiny public library in Mansfield, Mo. Lane, however, instead left the Little House rights to MacBride, whose daughter still owns them today.

MacBride began systematically renewing copyrights to the Little House books in the 1960s, and sold the Little House rights to television—turning it into the series that aired in the 1970s. Although the TV show departed in a saccharine way from the Little House books, it entranced another generation of Little House fans.

Clearly, the Little House ethic of self-sufficiency appeals to a much wider American audience than just one with libertarian politics. Pioneers could be cold, dirty, or hungry without whining. They faced down adversity. They made do with little. They respected the power of storms and the patterns of wild animals. The books inspired whole generations of women, and Americans of all political persuasions admire the tenaciousness of settlers like Ma and Pa Ingalls and their four daughters.

Lane must have known, as she redrafted her mother’s handwritten memoirs, that this notion of pioneer bravery—and the very real fortitude of the family—would prove an irresistible American theme. The result was a series of books that helped instill a deep national code of frontier values, including the notion that isolated Americans can thrive because the government leaves them to draw only on their personal energies and ethics. It’s an appealing idea, and it has become woven into our image of the pioneers. But it’s not the full story of what happened out there on the prairie.

About This Article

Stephen Heuser, formerly of the Boston Globe (and now at Politco), was my editor—one of the best I’ve ever worked with. I also thank Farah Stockman, columnist for the Boston Globe; she guided me to work my ideas into what you see here. This article first appeared in the Boston Globe’s Ideas section on Sunday, August 11, 2013. It covers some of the major themes in the book I’m writing about Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, who secretly collaborated on the Little House books for children. They wrote them together in Missouri and then by mail between Missouri and the East Coast between 1930 and 1943. The two women did not get along, and their partnership was very tense and resulted in the fracturing of their relationship. These children’s books have inspired generations of people who continue their devotion into adulthood. The love of the books is so strong that it has changed how Americans view pioneers.