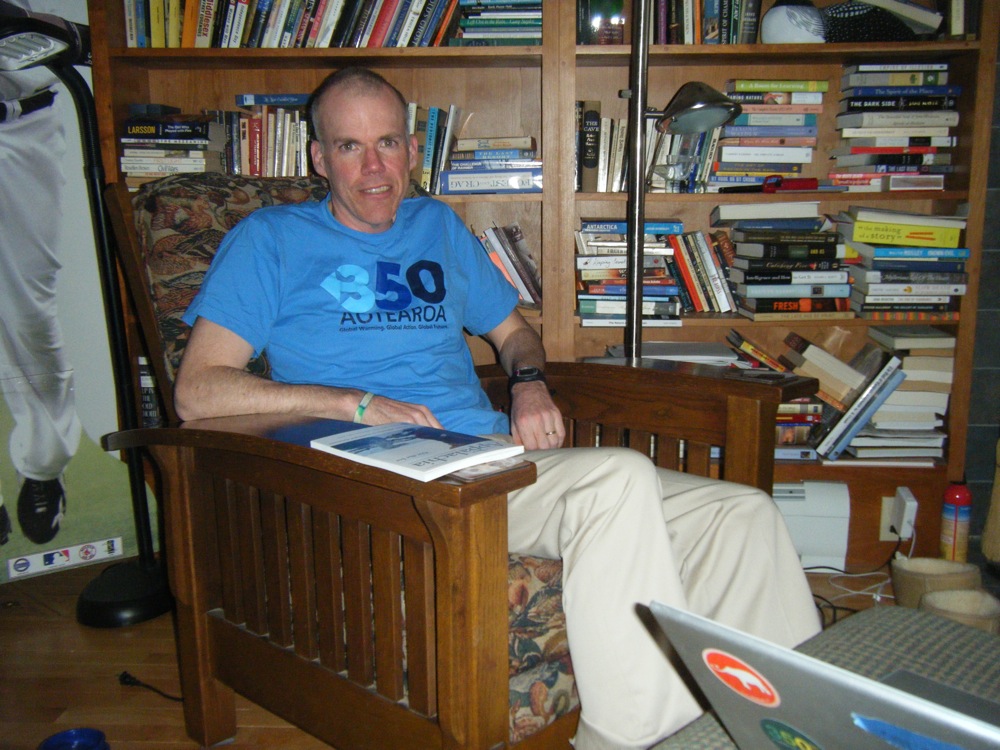

McKibben with the 350 logo T-shirt, at home in Ripton, Vermont

Nature Reports Climate Change

In his new book, environmentalist Bill McKibben says we must abandon the notion that economic growth and environmental sustainability are compatible — only then can we prevent a climate catastrophe.

In 1989, American environmentalist Bill McKibben wrote a book about climate change, for ordinary people. In The End of Nature, McKibben sounded one of the first warnings that the industrial age was altering Earth and argued that unless greenhouse gas emissions were cut back, the planet would change irrevocably. “I wrote The End of Nature and thought, ‘People will read this and be all set,’” he says. Governments would limit greenhouse gas emissions. Citizens would change their expectations. Some 20 years later, the global average temperature is still rising. So it’s perhaps unsurprising that McKibben’s latest book, eerily titled Eaarth, reflects a darker view. In Eaarth, McKibben writes that now it’s clear Earth will never be the same; it ought to be renamed.

When McKibben wrote The End of Nature, he was 27 years old and had just left his position as a staff reporter for The New Yorker to live in a remote area of the Adirondack Mountains in New York State, 15 miles from the nearest grocery store. Now he’s 49, and home for him is in the tiny town of Ripton, Vermont, where I visit him one day in late winter. There, he and his wife — writer Sue Halpern — and daughter live a low-energy life: their heavily insulated house is powered by grid-tied solar photovoltaics; they use a hybrid car and eat much local food. McKibben once ate only Vermont-produced food for most of a year. This is a lifestyle he has often sketched out for readers in earlier books such as Hundred Dollar Holiday, on enjoying Christmas without commercialism, and Maybe One, on his and his wife’s decision to have a single child.

In one crucial aspect, McKibben’s mission in Eaarth is much the same: to bring home to ordinary citizens on every continent, but especially Americans, that the party is over. He believes that far too few people paid attention to the warnings that were circulating 20 years ago and earlier, and as a result, the task of reversing the trend of temperature rise has become ever more difficult. He hopes that soon it won’t be practical for anyone to just jump on a plane for fun or take long showers or live in huge houses. Instead, he suggests that people travel vicariously on the Internet, make energy on their roofs and view local food production as the norm instead of a fad. But McKibben admits that time has also changed his message. Though he still urges people to scale back, he no longer thinks that such actions will be enough without major policy changes. “Never mind one light bulb at a time,” he says. He now hopes that the collective choices of individuals will push lawmakers to put a price on carbon, and that raising the price of fossil fuels will reduce emissions.

For McKibben, nothing less than a transformation in mindset is needed to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations to a level that will prevent dangerous climate change. It sounds gloomy, but in person McKibben is anything but. He’s casual, easy to talk to and kind. In Eaarth, he describes his vision for the planet by telling the stories of those who are already living that way. He hammers his readers with real-life examples: a Massachusetts bakery that wanted local wheat and talked 100 of its neighbours into growing it in their yards, and the city of Portland, Oregon, one of many to ignore the United States’ failure to sign the Kyoto protocol and pledge to meet its targets through cheap bus passes, 750 miles of bike paths, and other measures.

Back to basics

But with his easy manner also comes a sense of uneasiness that we’re running out of time and we’re unaware of the scale of the challenge. McKibben dismisses the American-as-apple-pie belief that economic growth can coincide with environmental responsibility. He mocks New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman as being a cheerleader for growth in his book Hot, Flat, and Crowded, and even takes a dig or two at Friedman’s wife’s family’s mall development business. In many respects, the world he outlines seems like a trip back in time: small communities living with local economies, with most people practicing part-time farming and producing power on rooftops near to where it’s used.

More radical writers than McKibben have warned of life as we know it coming to a crashing halt, and he refers to a few, among them E. F. Schumacher, author of Small Is Beautiful, and Paul Roberts, who wrote The End of Oil. But about five years ago, McKibben realized that he needed to go a step further than writing about climate change. While reporting a magazine article in Bangladesh, he came down with dengue fever and ended up in a hospital, where he cringed at other patients’ suffering. “Mosquitoes very much like the world we’re creating,” says McKibben, who was inspired by the experience to do something that journalists rarely do. He became an activist. Sitting beside his woodstove at home in Ripton, McKibben tells me that his transition to activism “happened fairly organically”.

Within a few months of returning from Bangladesh, he led a 1,000-strong protest walk through Vermont, demanding political candidates sign a carbon-reduction pledge. Two years later, he organized two rallies across the United States in which protesters called on Congress to pass meaningful greenhouse gas emission legislation. Next, McKibben telephoned veteran climatologist James Hansen, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute of Space Studies in New York, and asked him if he could identify the maximum concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide for a healthy planet. Scientists and others had previously talked of limiting greenhouse gas levels to 450 or 550 parts per million (p.p.m.) — roughly twice the pre-industrial level of 280 p.p.m. McKibben recalls that “[Hansen] called me back three months later and said, ‘We’ve done the work, and you’re not going to like it, but it’s 350.’” From there, McKibben went on to establish 350.org, a global campaign to find solutions to climate change. On the wall of a downstairs room in his house hang three large framed photographs from a day last October when people at 1,500 locations worldwide spelled out ‘350’ with their bodies and with signs: one group of 1,000 children in the Maldives, one group in front of an Egyptian pyramid, and the third a group in Mongolia.

In many ways, McKibben’s argument is simple: rather than give way to the inevitable, “we might choose instead to try to manage our descent”, he writes in Eaarth. But that means that ‘First Worlders’, particularly Americans, need to grow up and think in new ways, he says. Like many others, he makes the crucial point that alternative energy technologies and energy efficiency can’t replace fossil fuel if first-world economies continue to grow. “This is the biggest problem we’ve ever faced,” he says, looking intently out from his seat by the woodstove. “We’re clearly losing badly and need as much action as possible.” On 10 October, McKibben is organizing a global work party, a day on which people will insulate their houses, install solar panels and repair drafty cracks. “The message will not be, ‘This is how we solve the problem,’” he says. “The message is, ‘If we can do this, then the US Senate can.’”

About This Article

I had met McKibben twice, briefly, and he had written for the journal I edit, Appalachia. I was intrigued with his decision to become an activist. He told me that if he were a newspaper beat reporter, of course he couldn’t be staging demonstrations worldwide. This story first appeared on April 22, 2010, online and in print, in Nature Reports Climate Change, published by the journal Nature in Britain. It can be found online here.