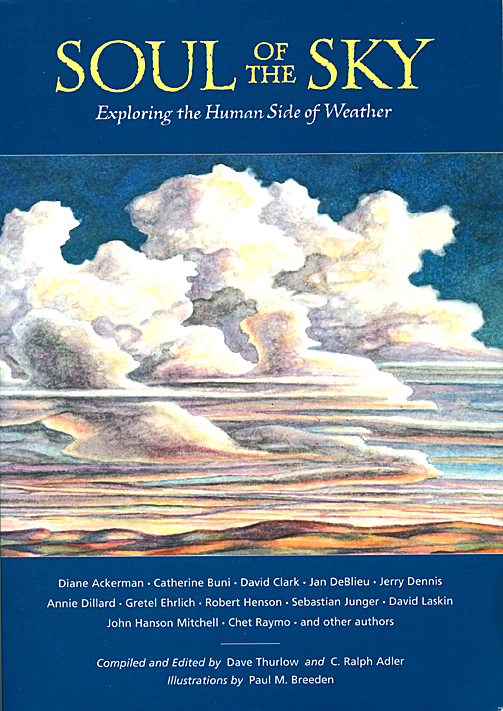

Exploring the human side of weather

Soul of the Sky is a different kind of weather book. It’s not preoccupied with charting fronts, defining what an isobar is, or trying to get you to memorize the conversion formula from degrees Centigrade to degrees Fahrenheit. Instead, it’s a collection that illustrates how the weather can inspire and terrify, connect us and urge us on to new adventures, and invite us to gain a deeper appreciation of how weather and climate affect our everyday lives.

Essays by Annie Dillard, Gretel Ehrlich, Chet Raymo, Jan DeBlieu, Dave Thurlow, Eric Pinder, Robert Henson, David Laskin, Mary Reed, Christine Woodside, Peter Felknor, Jeff Grabmeier, Robert Irion, John Hanson Mitchell, Paul Breeden, David Clark, Diane Ackerman, Craig Werth, Catherine Buni and Ralph Adler.

Soul of the Sky was the companion book to the Observatory’s former nationally syndicated radio program, the Weather Notebook. The National Science Foundation supported the book. Compiled and edited by: Dave Thurlow & Ralph Adler. North Conway: Mount Washington Observatory, 1999. Paperback, 150 pages. But it from the Mount Washington Observatory, Barnes and Noble, or Amazon.

Excerpt from my essay, Rage on Grassy Ridge

To my list of fears — the dark, strange dogs, wasps, and ladders — I added a dread of thunderstorms after the night of April 22-23, 1997. My two young daughters and I spent that night inside a tent while a thunder, winds, and rain whipped across Grassy Ridge, an open saddle at 6,050 feet in the Appalachian Mountains at the Tennessee-North Carolina border.

The gray clouds rolling in that evening did not look threatening. It was not cold when we left, but the temperature dipped as the storm thrust in to meet our campsite. Long stretches of wind and driving rain hit between about midnight and dawn. I sat up most of the night trying to stop the tent from swaying. I stretched my arms into a beam to hold up the tent while the storm lashed from the northwest at a 45-degree angle against the nylon.

Going into that night, I had slept in a tent in the Appalachian Mountains between northern Georgia and central Maine probably 45 times, and in trail-side shelters at least 80 times. I’d never had rain like this. In the spring of 1987, the year I hiked the entire Appalachian Trail, I trudged through daily afternoon thunderstorms for about 10 days. During one deluge, lightning ripped open a tree a quarter mile north of where I stood huddled with my friend Cay. At the crash of electricity destroying the tree trunk, I practically jumped into her arms in fear. But a moment later, we started hiking again. We saw the giant shards strewn down the forested incline. I wasn’t scared, just impressed. I liked thunderstorms. I relished the sweet smell of a downpour that breaks long days of strangling heat.

I drove more than 800 miles to the grassy highlands of Tennessee and North Carolina from our house in central Connecticut to make reality out of an idle dream. “Did you know there are mountains with just grass growing on top?” I asked Elizabeth and Annie, ages 8 and 6, one night as I was putting them to bed. One of them said, “I want to see them.” “I’ll take you there someday,” I promised. The nightlight cast a comfortable shadow on their round cheeks.

About This Book

The essay I wrote for this book was my first major sale as a freelancer and my first sale done by email. Ralph Adler, the editor, had posted an online ad for contributions. I wrote the essay in a few days after he extended the deadline. I still remember jumping around the office I was then renting on Main Street in Deep River after receiving the acceptance email on my old laptop.